It was 1979 and speedway legend Terry Betts had just quit the sport he loved at the age of 36.

The risks that first attracted him to the oval as a fearless teenager had become too great when he had a serious crash at Reading – a sign not to push his luck too far.

He had a young family to think of, new priorities and a new life to look forward to after two decades of domestic and international success.

“After I swallowed my tongue at Reading I thought maybe it was a warning – this seems the time to give up,” he says at his home just south of Cambridge, squeezing into age-stiffened racing leathers for our photoshoot.

But he knew how easy it would be to get drawn back into the saddle, that the offers would come – and that he’d find them hard to resist.

So he systematically dismantled all the bikes he’d kept from 20 years in the sport, stored them away and kept his distance from the tracks where he’d made his name.

“When I packed up I made sure I had not got any bikes ready to race,” he says, just a few pounds off his racing weight at the age of 74.

“I knew what would happen – six months down the road someone’s going to talk me into riding. Someone will come along with an offer and I would be doing it for the wrong reasons.

Terry ran his own garage after retiring from speedway racing

“You’ve got to be serious about it, it’s not something you can play at. That’s when you will get hurt, when you’re not fully committed. I had a good run at it and it was time to move on and keep right away from it.”

And so Terry did, buying and running a garage and building his own home on the six acres of land that came with it.

But about 10 years ago, encouraged by his son, also Terry, it was time – and safe – to start rebuilding, to reconnect with the bikes that carried him to international stardom.

“It was long enough after I retired that I was not going to be taken back into it,” he says. “My son, who was only four when I stopped riding, was the one who encouraged me to do the bikes that were just sitting there going rusty.”

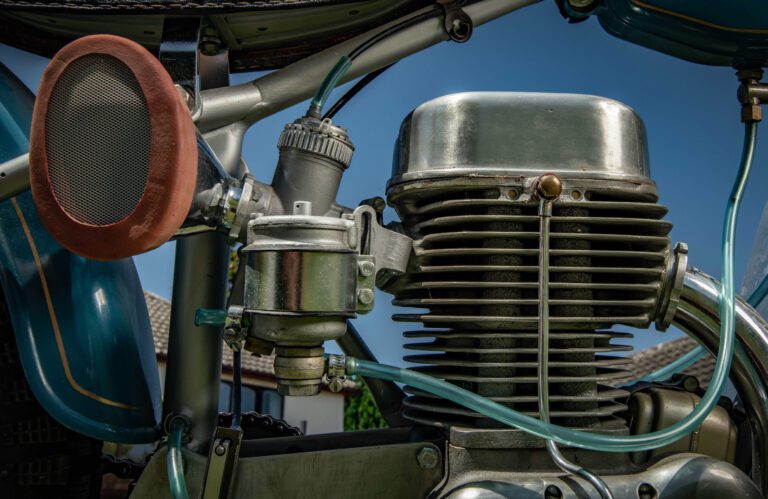

Of all the bikes he kept, the first to be restored and closest to his heart is the Jawa on which he won the 1972 World Pairs title with Ray Wilson in Sweden.

Bought with his own money for £491 at the start of that season, sitting astride the Jawa’s banana seat now and grabbing those wide handlebars throws Terry right back to the second golden age of speedway.

“It takes me back to travelling on the old ferry to Sweden with Ray, with the bike in the boot of a Mercedes, and coming back we had won the World Pairs,” he says.

“No-one had given us much of a hope. It was more or less expected that the Swedes were going to win it.

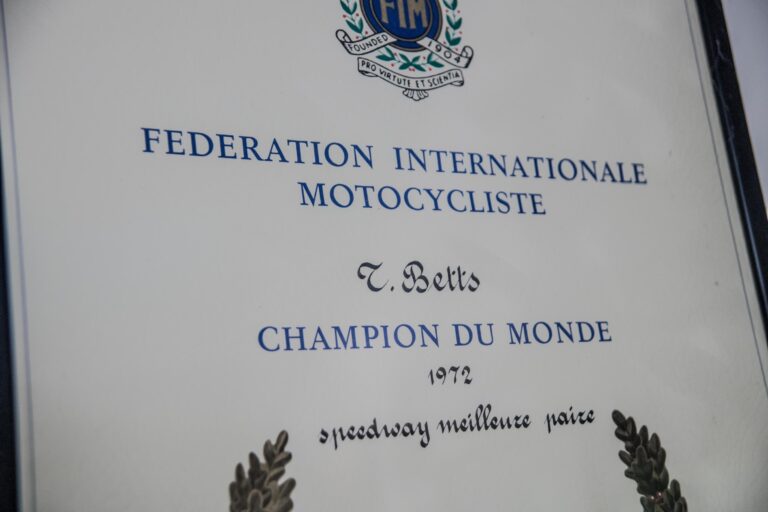

Biggest achievement in speedway

“It’s something I can always go and have a look at and remember being in Borås in Sweden with that bike. That was probably my biggest achievement in speedway.

“Selling it now is not something I would even consider. I can’t see the point unless I was on my last uppers, and Terry says he will always keep hold of it.”

Jawa bikes revolutionised speedway in the late 1960s, the Czech-made machines lighter and faster than the British-made JAPs (J A Prestwich) on which Terry started his career as a raw 16-year-old at Norwich in 1960.

“The advantage was people could go and buy a bike that, almost off the shelf, was capable of winning the world final,” he says.

“With a JAP it would take two years to learn how to ride it and two years to find out how to make it go. On a Jawa a lot of people could be competitive without it costing them a fortune.”

As well as the ‘72 bike, restored to as-new, as opposed to racing, specification, Terry still owns several other racing bikes, including the one on which he competed with a broken collarbone in the 1974 World Final, and the last bike he rode during his one season at Reading.

“They’re the ones that mean something to me, which is why I kept them,” he says. “Having done the ‘72 bike I thought I might as well put the others back together.

“The frames have all been away to be sandblasted and I’ve sorted all the engine bits out.”

The one bike Terry didn’t keep hold of was a JAP, so he decided to buy one instead, finally finding a 1940s example ridden by Australian champion Vic Duggan.

Buying a J. A. Prestwich bike years later

“I started with JAPs and always wanted one, but could not find one with an Erskine frame,” he says. “I got rid of mine years ago. You couldn’t give them away because no-one wanted them.

“This one came up owned by a guy in Kent. It had previously been on display in a shop window in Birmingham, and after he bought it he would take it to shows and let people see it.

“But he couldn’t ride it on the road and wanted to sell it. Now some Aussies have found out I’ve got it and are pestering me and want to buy it!”

Well-known throughout his career as one of speedway’s good guys, always happy to chat with fans and sign autographs, Terry remains as popular today as he was in his heyday, voted the best King’s Lynn Stars rider of all time in 2005 by fans of the club he served for 14 years.

Now, sitting at his dining room table with Sue, his wife of 53 years, looking out at the Jawa on the lawn, he takes me back to the very beginning when, as a nine-year-old, his father would take him to watch the likes of Jack Young and Freddie Williams at West Ham in the early 1950s.

“The smell of the Castrol R was just unbelievable”

“I can always remember going there under the floodlights, and the smell of the Castrol R was just unbelievable,” he says.

“I decided that was what I wanted to do, something that was risky. It was a really dangerous sport and a lot of people got killed in those days, one or two a year. It was the thrill of the danger that attracted me to it.”

With no junior competitions, Terry would practice slide an old BSA around the garden until, at the age of 16 – the minimum age for racing – his father bought him a JAP from rider Brian Meredith at Rye House.

“It was too big for us to go round the garden, so I learned to slide it on the perimeter track of an old wartime airfield that was not far from us,” he says.

“Then my dad took me to Rye House to a practice day. I’d never been on a speedway track, but I thought ‘this is easy’ because I’d learned to slide on tarmac. Mike Broadbank was running the session and he said to my dad, ‘who does he ride for then?’ Dad said, ‘it’s the first time he’s been on a speedway track’.”

Broadbank wanted to sign Terry there and then, but his father said it was too soon, allowing him to compete in an open meeting in a pair with Meredith.

“I crashed every race!” laughs Terry, who quickly found that sliding on your own was a world away from the helter-skelter sprint to the first bend of a competitive race.

Terry and his father began making the trip up the then single-carriageway A11 from their home in Old Harlow to Norwich to watch the Stars compete in the National League.

A speedway star was born

It was there that a star was born, spotted while riding around the track after the meeting while the national anthem played.

Terry was invited to compete in the junior handicap race, and it quickly became clear the Norwich Stars had something special on their hands – a young tyro who would soon compete alongside established superstar Ove Fundin.

“I went off the gate and won my race, and the next week they put me 10 yards back and I won, and each week they put me further and further back but I kept winning,” remembers Terry, then still only 16.

“After that, they put me in the team, initially as a reserve.”

Terry’s increasing speedway commitments saw him quit his job as an apprentice mechanic at his local Vauxhall dealer.

“When I went to Norwich they gave me an ultimatum because I started having too much time off,” he says. “They said ‘make your mind up, are you going to do speedway or work here?’

“I thought, you only get one opportunity – I can come back and be a mechanic but I can’t come back and be a speedway rider, so I packed it in.

“My dad said he would back me for two years and if I hadn’t made the grade by then I was on my own. He was always of the opinion that if you’re going to be any good you will show signs in the first two years.

“My attitude was ‘I want to be a speedway rider and I am going to do it’. I loved the fact I could be getting paid for something I loved doing.”

It took far less than two years for Terry to prove himself.

To gain experience, he combined riding for Norwich with a spell at Wolverhampton in the breakaway, and booming, Provincial League in 1961.

“I was riding four to five meetings a week at both, but in 1962 they stopped you riding both leagues so I stayed at Norwich and became a heat leader,” he says.

Dudley Jones, writing on the Speedway Plus website, remembers watching an 18-year-old Terry take on a Southampton side at The Firs including world speedway stars Barry Briggs and Björn Knutsson.

Wild and often frightening lad

“Terry scored nine, including wins over Briggo and Knutsson – this wild and often frightening lad was going places – if he stayed alive!” writes Jones.

“With Terry in 1962 you never knew what to expect, or whether he would stay in one piece. In those days he was already the favourite of the teenies, and wore what appeared to be turned down wellies, with green and yellow (what else) football socks.

“As to style, I would best describe it as wind the throttle on and hold tight. It was at this time that I learned how to hold my breath for more than 70 seconds while I willed that Terry would stay on his JAP for four laps.”

Terry had the speedway world at his feet, but a row over money with Norwich nearly saw him lost to the sport for good.

“I went to Belle Vue and got a 15-point maximum, beating (former world champion) Peter Craven,” he says. “That’s when I started spending a lot of money having engines done and that’s when I started wanting more money.

“Norwich was really bad on engines, a really fast track which was blowing the old JAPs up – I said I’ve got to have more money or I’ll pack up.

“It was July or August 1963 and I said ‘look, I’m packing up’. They said ‘no you won’t, you love it’. I said ‘I bloody will!’ They took me to court and I got banned for a year, effectively because I didn’t turn up.

Meeting Sue after a speedway ban

“I thought ‘fair enough, that’s me finished with speedway, I’ll go car racing’ and I built a saloon car and went car racing at Snetterton.”

The break from speedway had one happy side effect, however.

“He didn’t have speedway, but he got me!” says Sue, who met Terry at a pub in Epping during his speedway sabbatical.

“We probably wouldn’t have met otherwise, because I was never around locally,” says Terry. “On Saturday nights, instead of doing speedway or doing my bike, I ended up going to pubs and clubs.”

In any event, despite large crowds, the Norwich directors controversially sold The Firs stadium for development just over a year after Terry walked away, ultimately paving the way for his return to a new track in a glorious new era for speedway.

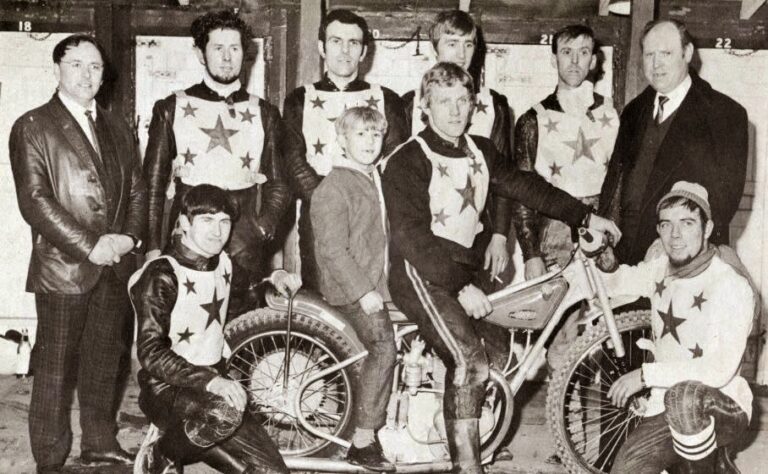

That Terry revived his career at King’s Lynn, at a run-down dog stadium on the Saddlebow Road, was entirely down to the persistence of one man: Maurice Littlechild.

With Cyril Crane, Littlechild took advantage of the demise of the Norwich Stars to bring speedway to the West Norfolk market town and port, not only taking the Stars name but their yellow and green jackets and various pieces of equipment, including the old floodlights from The Firs.

“Maurice came round and said ‘how do you fancy doing some open meetings in 1965?’” says Terry. “I said ‘King’s Lynn? Where the hell’s that?’

Maury was a real persuader

“I told him my dad had bought a garage at Dunmow and I was working there, so I couldn’t do it. But Maury was a real persuader, he said it would fit in because it was only once a fortnight.

“They were laying the track and Colin Pratt and myself went down there and we tested the track out. I still had the old JAPs I raced at Norwich and rode one in the very first open meeting in May 1965 at King’s Lynn.”

After more than a year out of the saddle, Terry won that meeting, and suddenly the word was out: Betts was back.

“It all went silly. All the tracks in the country wanted me to come out of retirement,” says Terry. “King’s Lynn wasn’t in the league then, but Maury said ‘next year we’re hoping to go in the league so don’t go signing a contract with anybody else’.”

Terry was loaned to Long Eaton for the 1965 season, a campaign interrupted by a broken leg after a crash at Poole – the plaster had only been off for three days when he walked down the aisle with Sue.

Didn’t that worry the new bride? That her husband – a mechanic when she met him – was about to rejoin a sport when the ‘new’ Stars were granted their league licence where risks to life and limb are an occupational hazard?

“I’m not a panicker”

“I was worried, but he was never frightening like some of them can be,” she says. “I’m not a panicker, and most of the riders respected him so they didn’t try to fence him.”

“There are risks,” adds Terry, but then that was what attracted him to the sport in the first place. “I’ve had broken arms, legs, you name it, over the time. Arms and legs you can mend but I said if ever I started knocking my head I’d pack it in.”

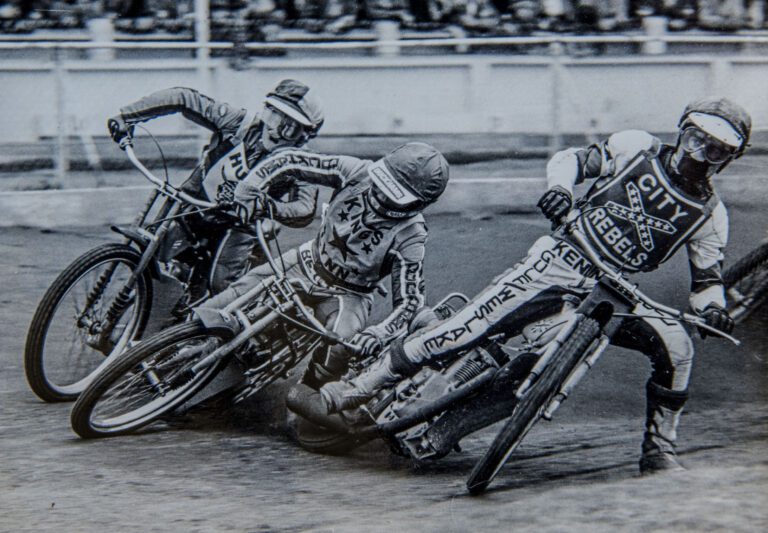

The King’s Lynn Stars duly got their licence and, with the amalgamation of the national and provincial leagues, this was boom time for British speedway.

“It used to be jam packed – there’d be 10,000 people there,” remembers Terry. “We had to get there early and go in the back way to get in they used to be queued up so far.

“It was new and it attracted a lot of people. We were all in our early 20s and most of the crowd were too – everyone grew up with it down there, and I knew the spots where they all stood. People would be in the same place week after week – you knew where to look for them.

“They asked me if I could play football for King’s Lynn because of the amount of people that would turn up for charity matches when I was playing.”

During 14 seasons at King’s Lynn, Terry became a living legend at Saddlebow Road, earning international recognition at the 1966 World Team Cup, finishing fourth.

The following year, he was knocked unconscious by a bottle thrown from the stands while representing England in Australia, an incident that made national news at home and abroad.

It was November 11 at the Sydney Showground, and Betts had played his part in a thrilling 54-53 win for the visitors when one of the 30,000-strong home crowd hurled the glass bottle towards the track.

“I thought a bomb had gone off”

“We’d won the first test and went out on the lap of honour,” says Terry. “I looked round to see where the other boys were and thought a bomb had gone off. Someone in the top stands had thrown this bottle and it hit me right in the side of the face and slit my eyebrow.

“I fell on the track. They thought I had lost my eye. I have no recollection of it beyond thinking a bomb’s gone off, bang, and the next thing I knew I was in hospital getting stitched up.

“In the crowd, it all kicked off. The crowd attacked him, and two off-duty police officers said if they had not stepped in they would have killed him. After that, the Aussies couldn’t do enough for me, everywhere I went.”

Terry was back in action just two weeks later, and rode in every round of the five-test series as an England team inspired by brothers Eric and Nigel Boocock returned home with a 3-2 series win.

By now, Terry had swapped the heavy JAP bikes for Jawas, buying his first from fellow rider Barry Briggs, who had secured the sole importer concession from what was then Czechoslovakia.

“You could only get them from Briggo,” he remembers. “He took the agency on them when no-one knew what Jawas were. If he found out you’d bought one in from Czecho, if you wanted any bits you could not get them.”

Although the crowds were bigger than they are now, and speedway riders were becoming big stars, they were still largely responsible for their own bikes, including transporting them from meeting to meeting.

“Only the top guys had mechanics”

“Only the top guys, like Fundin and Briggs, had mechanics, everybody else did their own,” says Terry. “In the early days you took one bike racing and that was it.

“The magneto would go on them, and you’d borrow someone else’s bike for the race. Colin Pratt was in the away team and he would borrow your bike – I lent my bike to various different people riding for the opposition.

“It was totally different. Now it’s like they’ve got a bike for every race.”

There were no trailers or transporters until riders started to receive sponsorship in the early 1970s.

“I remember removing the boot lid of an Escort and standing the bike in the boot. Howard Cole had a Mini and he’d sit his bike on the open boot lid and go all over the country,” says Terry.

“Then I had a Citroen DS. I used to take the rear window out, take the boot lid off, cut down the parcel shelf and put the bike in the back. When it rained we’d get wet feet.”

As well as the World Pairs title, Terry was part of the World Team Cup winning teams of 1972 and 1973, but it’s a less-heralded trophy that means as much as any world crown.

“One that means a lot to me was winning the first Littlechild Trophy at King’s Lynn,” he says. “Maury was the reason I came out of retirement. He was not a promoter to me, he was my best friend really and when he died in 1971, to win it was something that meant a lot to me.

“Maury brought speedway to King’s Lynn and was a big part of my life.”

Terry was granted a testimonial at King’s Lynn in 1975, and continued to be the heartbeat of the team until switching to the Reading Racers for a single season in 1979.

“After King’s Lynn I didn’t enjoy it,” he says now, with 649 meetings at Saddlebow under his belt. “Reading looked after me and paid me good money, but I was doing it all for the wrong reasons, and that’s not why I did speedway – that was a bonus.

“I felt like a guest rider”

“I was at King’s Lynn too long to go and ride for somebody else. I felt like a guest rider and I was not enjoying it.”

For many professional sportspeople, retirement can almost feel like bereavement, an entire life of camaraderie and the buzz of competition ripped away overnight, to be replaced by, what, exactly?

“I was in speedway for 20 years, and it all went too quick really,” he says. “I loved every minute of it. It was brilliant, the fact that I could earn my living doing something I loved.

“Then you think ‘what am I going to do?’ All your friends are connected to it. All these people you see all the time and you’re not going to anymore.”

While building up his garage business, he tried his hand at team management at King’s Lynn, but it was no replacement for the thrill of racing.

“I did it because King’s Lynn were in a bit of trouble, but it wasn’t the same,” he says. “Trying to motivate riders – if you’re not motivated when you get there, if you don’t want to win, you might as well go home.”

Terry didn’t entirely keep away from speedway though, turning out in the Golden Greats meetings run by his great friend, Barry Briggs.

Rupert Jones, who had marvelled at the skills of the 18-year-old Norwich starlet all those years ago at The Firs, was in the crowd at Coventry in 1988, nine years after Terry retired.

“Terry was in a class almost of his own,” he writes. “He went round Coventry, after nine years away, as if he’d never retired. His times were league times, and his match with Peter Collins (who had retired only the year before) was great to see.”

For most of the last 40 years, though, Terry has been busy developing his business on the six acres of land he bought in 1979.

“I needed something to do for the rest of my life,” he says. “When I took the garage on it was a Leyland franchise employing seven blokes.

“I hated it! I had so much hassle, so I rented it out and started selling commercial vehicles.”

When the lease was up, Terry was refused permission to build housing on the land, so constructed business units to rent out, and at the same time started building his own house on part of the land.

Nostalgia for the speedway racing days

Its name? “It was all down to Saddlebow Road, so we called it Saddlebow House,” says Terry, whose office is an Aladdin’s Cave of speedway memorabilia, photographs and trophies, including the yellow and green Stars bib he dons for our pictures.

Terry junior helps his dad dig out an old pair of boots and a vintage Bell racing helmet and, but for a few more wrinkles around those clear blue eyes peering out from beneath the visor, it could be 1972 again.

Slowly but surely, the bikes once put aside to keep Terry from temptation are being brought back to life.

And none is more special than the Jawa on which he now sits, smiling and reliving the glory of Sweden.

Photographs by Simon Finlay.