As a teenager in the early 1960s, when British bikes still ruled the roads, Bob Warner only had eyes for the big Harleys from across the Pond.

It was an era when motorbikes, or scooters if you were on the other side of the mods and rockers divide, were the only affordable mode of transport for youngsters looking for freedom.

Like his classmates, the 14-year-old Bob would count the birthdays until he could hit the road on his own bike.

“At school, some of the other boys were on about the Triumphs, Nortons and other British bikes,” he says.

“But I’d seen pictures of Harleys in magazines and had decided that was what I wanted.”

Of course, even in those less safety-conscious times, the big Yank bikes were out of the reach of a 16-year-old yet to pass his test, so Bob joined his mates and bought a 1959 BSA A7 twin, at 500cc still a meaty machine for a teenager still at school.

Dreaming of owning a Harley Davidson

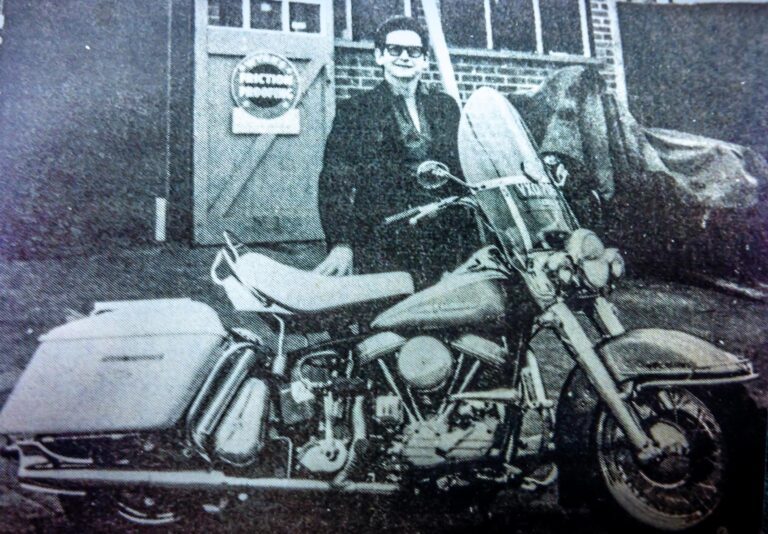

Bob would have to wait three more years to realise his dream of owning a Harley Davidson, forking out £148 for a 1946 ex-military WL 750 imported by legendary dealer Fred Warr and restyled and repainted for civilian life.

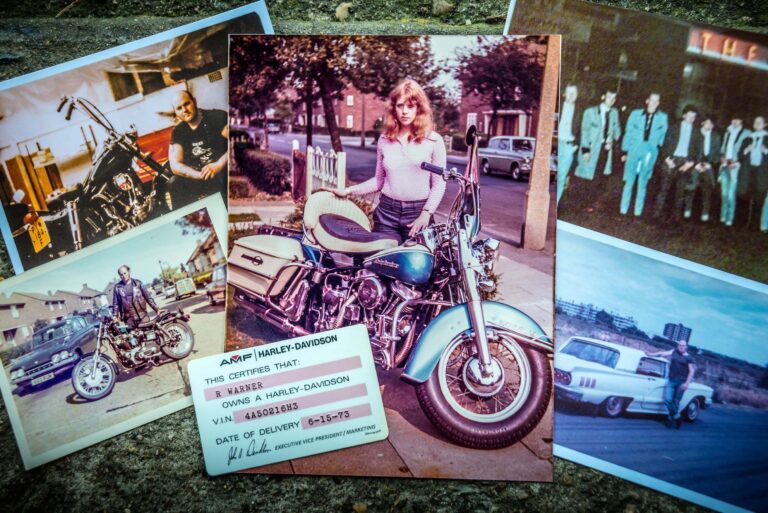

Other Harleys came and went before Bob, now 68 and a retired motorcycle mechanic and lorry driver, settled on the perfect machine in August 1974 – a 1958 FLHF Duo-Glide, the very first of the model imported into England and still taking pride of place in Bob’s garage after more than four decades.

“To me the Duo-Glide was the top of the range of what Harleys could offer and it was what I wanted,” says Bob from his home in Spalding, Lincolnshire. “In the 60s they came out with the Electra Glide, but they often had problems with the electric starts. I used to be repairing them all the time as people couldn’t get fired up on the electric start, so they would bring them down to me.

“For me, there was nothing to upgrade to so I never thought about selling it and I wouldn’t sell it now. One chap did phone me up once and offered about £11,000, but it’s worth more than that and worth more than money to me anyway.”

Bob grew up in west London, and came of motorcycling age in the last years of the biker cafe culture that saw hundreds gather at the iconic Ace Cafe on the North Circular, the Busy Bee at Watford and the Cellar Cafe at Windsor.

The forecourts thrummed to the sounds of mostly home-grown bikes, while inside youngsters would drink tea, coffee or Coke and listen to rock and roll on the jukebox.

Talking bikes all night long

“We went every night down the old cafes,” says Bob, initially riding the BSA. “There were dozens and dozens of bikes, all night long.

“All my money went on it. We weren’t going to dances, weren’t going to pubs. We’d spend the night sitting at a cafe making a cup of tea last, just talking bikes all night long.

“Nobody was drinking beer. People can’t believe it now, but bottles of Coke were twice the price of a mug of tea, so we tended to have a big mug of tea. We were all apprentices and couldn’t afford a Coke in those days.

“We’d just be in and out, back and forth just generally hanging about there all night. If something interesting turned up, or an extra noisy bike, people would go out and have a look.”

The Ace was nearly 25 miles from his home, but with petrol only 4s 10d a gallon, and the BSA doing 80mpg, a tankful costing about £1.50 would last a week.

“That was still half a week’s wages,” says Bob, who had switched to his first Harley by the time the original Ace closed its doors for the last time in 1969.

“I drove my mates who I was hanging about with mad about it. Fred Warr was getting bikes from war surplus and we used to go there at night and look at the Harleys in the window on the King’s Road.

“My mates were all British bike blokes and they could not understand why I was looking at these antiquated old Harleys. To me, that was the attraction of it all – it was totally different. There were hardly any about on the roads, you’d never see them around at all.”

The old military Harley, with its foot clutch and hand gears on the petrol tank, ensured Bob stood out on the cafe runs in the last throes of the rocker era.

Last night at the Ace

“It was all dying a death by then,” he says. “Towards the end in the week days maybe 15 or 20 people might find their way there. It was not like it was in the heyday. They were the good old days.

“On the last night at the Ace there weren’t many people there. I was there with about eight or nine mates, and half a dozen other people. Just a few die-hards.”

Another favourite haunt was the Old Manor Cafe at Camberley, a good 40 miles from his home at Hayes.

“I went everywhere on that bike,” says Bob. “Every night I used to be flying over there. I frighten myself now thinking about it – no mobile phones, no-one in the AA or RAC.

“Most of the time I was by myself, so if I’d have broken down at any time I’m not sure what I would have done, but when you’re younger you don’t think along those lines.”

Bob soon added a 1000cc Knucklehead with a 1947 OHV engine and a 1952 Hydra Glide body, before selling both bikes and upgrading to a 1957 1200cc Hydra Glide, which he owned until 1972 when a low-slung Sportster caught his eye.

“Never seen anything like it”

“I’d gone to Fred Warr’s and they had a 1972 Sportster in there for a service, and we’d never seen anything like it,” he remembers. “It had a massive engine, tiny little petrol tank and tiny little seat. When I sat on it my bum was nearly on the floor. I thought ‘I’ve got to have one of those’.

“I put in an order for a brand new one but, in those days, Harleys were only producing limited numbers allocated for export to different countries, so there was a year’s waiting list.

“It was the first year they made the XLCH Sportster, and only two were ordered in the UK that year – mine and an XXCH ordered by a girl.”

Bob’s hopes of having the bike in time for the International Harley Rally, being held at Hereford racecourse in 1973, were dashed by a dock strike.

“I was desperate to get this bike in time, but it was sitting at the docks in a crate, so I had to go on an old Triumph I had,” he says.

“Noisy little racing Harley”

The bike turned up about 10 days later, this “dinky bike with a massive engine”.

“It was a noisy little racing Harley,” says Bob. “It had a banana seat with no back rest and it was around the time I started going out with the wife (Fay). She had to get on the back of this bike. Every time we went anywhere she ended up with a sore bum, but we still went to the rallies.”

After a year, though, Bob – and almost certainly Fay – had had enough.

“It was a fun bike to fly about on, but I thought a year was enough,” he says, his eyes now fixed firmly on the bike that would stay with him forever, a 1958 Duo-Glide.

“It had been offered to me in 1970 when I had my Knucklehead – a chap wrote to me and wanted to part exchange it plus cash, but I wasn’t interested at the time,” he says.

The bike was sold instead to Southport, where it again crossed Bob’s path on a rally, before it found its way back to north London and was again for sale in August 1974.

“I shot down to Fred Warr, who said he’d buy the Sportster back for more than I paid for it,” says Bob. “I paid £1,250 for it, which was an astronomical sum in those days. You could buy a BSA for £30 or £40 secondhand. That was when I started wheeling and dealing in bikes, and you could pick up those bikes for next to nothing.”

The Duo-Glide was now 16 years old, but still set Bob back £1,125.

“Horrified with the money I was spending on it”

“My dad never had motorcycles, and he was horrified with the money I was spending on it, but they were very rare and this bike was the full business,” he says.

“It had got all the saddle bags and crash bars and was exactly as you would imagine a US Harley Davidson to look in those days. I’ve stuck with it ever since.”

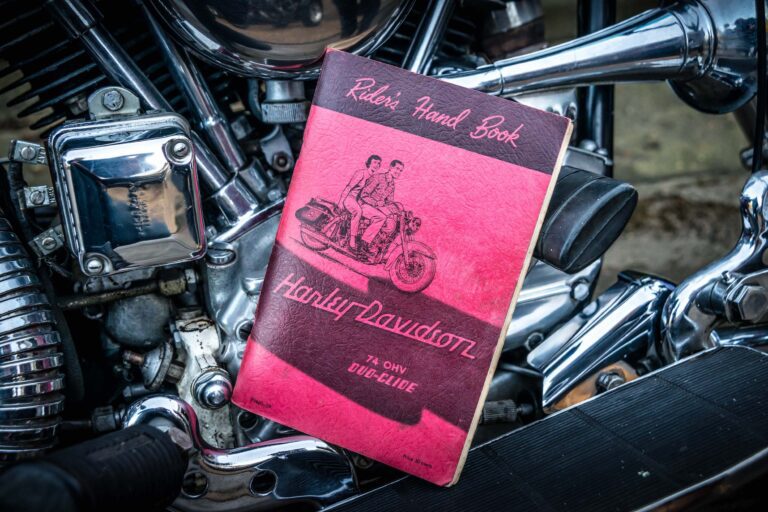

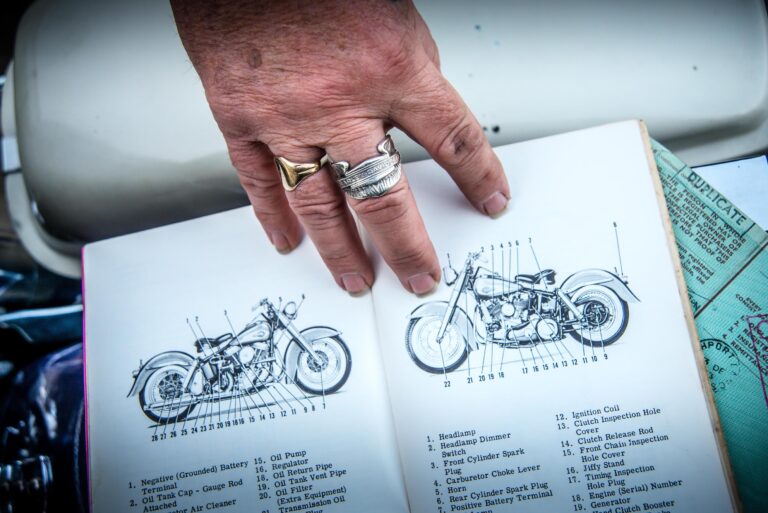

The Duo-Glide, launched in 1958 to replace the Hydra Glide, is considered to be one of the most beautiful Harleys ever made, featuring a rear swingarm suspended by a pair of coil-over-shock suspension units, giving the bike its name, along with a Panhead engine and frame flourishes.

It was equipped with a dual fishtail exhaust, chromed oil tank, kick-start pedal and handle grips, and featured an unusual speedometer that dropped the zeros to read 1 to 12 to eliminate clutter.

“Fay was pleased, definitely!” says Bob, who bought an existing motorbike repair business the following year, turning his passion into his business.

“The Hydra Glide had telescopic forks but still had a rigid frame, and the whole bike skipped and bounced down the road on bumpy roads. The Duo-Glide was much smoother.”

By the age of 26, with a decade of riding under his belt across the UK, Bob had no qualms about making a trip to visit friends in Holland on the big Harley in March 1975. After all, winter was over, right?

Wrong – March 1975 was unseasonably cold, and the trip was to take on epic proportions after a promising start.

“It was used every day, whatever the weather”

“I’ve never been one to only ride on a Sunday,” says Bob. “It was used every day, whatever the weather, to work and back and out every night, so I was pretty confident.”

The journey took the couple to Dover, on the ferry to Zeebrugge, and then through Belgium and on to Holland.

“It was nice weather until we got to my friends’ right over the far side of Holland and it snowed,” says Bob.

“We were absolutely frozen and they had snow for two or three more days. I remember riding down to this Harley dealers, with snow at the side of the road. This Dutch Harley dealer thought we were mad.

“But the return journey was the scary one.”

The couple set off to catch the 9pm Zeebrugge ferry, but a wrong turning saw them heading to Rotterdam.

“We should have turned off earlier, and ended up going across all these bridges that span the inland waterways.

“By now it was pitch black and the Harley only has 6V lights, like a tiny little yellow candle. I was peering over the top of the little windscreen, goggles down and I’m surrounded by lorries.

“Getting near to Belgium I was getting low on gas, but couldn’t find any garages open. Most of the garages there closed early because of hold-ups and robberies.”

They made it to the top of Zeebrugge High Street, in the pouring rain, when the Harley finally ground to a halt.

“We pushed the bike a bit, and found a garage that was closed,” says Bob. “There were four or five pumps and they weren’t locked. I got a tea cup of petrol from what was left in the nozzle and tube from each pump.

“That got me down the High Street in Zeebrugge to the entrance, where I ran out again. The weather was getting really bad and they weren’t letting the ferry sail because the Channel was so rough.

“It was still chucking with rain, and we managed to get under the front wheel arch to keep out of the rain. Our leather gloves were soaked right through.”

At midnight, Bob and Fay were asked to load the bike first, pushing it down the ramp and into the hold.

“It was a terrible crossing”

“The weather was a bad as they could sail in,” says Bob. “We tied the bike down and sat on the ferry. It was a terrible crossing, I’ve never been on anything so rough; there were people throwing up left, right and centre.

“On the other side they wanted me to get the Harley off first. There was a ramp going up at an angle and the blokes helped us push the bike up, then left us to it. They were concerned I had no petrol.”

Before Bob could fill up at a garage just outside the dock area at Dover, he and Fay pushed the bike through the customs ‘nothing to declare’ lane, where they were told the box of cigars and two litres of rum they’d brought back was “technically smuggling”.

“We thought you were allowed one litre each, but they said it was between us and we’d have to pay for it,” says Bob.

“I only had 30 shillings left on me and I needed three or four gallons of petrol to get myself home. It left me just enough to get some petrol.

“We pushed the bike all the way to the garage and filled her up. By now snow and frozen rain was coming down. We stopped wherever we could under bridges, took our gloves off and warmed them on the engine for 10 minutes and off we go again. We got home at 8am, totally frozen. Fay had to go and sit in the bath to warm up.”

Bob and Fay also attended the infamously tough Dragon Rally, held in winter in North Wales, and, though the couple’s long-distance treks are a thing of the past, the Harley is still a regular sight on the roads of Lincolnshire.

“It attracts a lot attention – everybody is surprised at how old it is,” says Bob, whose love of Americana extends to cars, having owned a 1960 Ford Thunderbird, an Oldsmobile from the same year, plus two Chevy Impalas, from 1959 and 1964, while a 1988 Ford F350 Dually truck currently sits on the drive.

“It’s all about having something different. The American cars from that era look as good on the inside as the outside.”

So what does the future hold for the Duo-Glide, a timeless classic from the golden era of motorcycling?

“A lifetime of memories”

“I’ll always keep it,” says Bob. “It’s got a lifetime of memories, and I don’t like the new Harleys – they’ve lost a lot of character and don’t have the same sort of noise.

“Mine is an old-fashioned, traditional bike. It’s comfortable, it goes down the road, it will do 100mph, and loaded up with all the bits and pieces it will go along happily at 50-60mph.

“Now and again, like any old bike, it can be a bit temperamental. It either starts first kick or sixth or seventh kick. But normally it’s as good as gold.

“My son, Ben, thinks it’s his. That’s what he tells everybody, that I’m looking after his bike!”

Ben, 32, rides a Harley trike built by father and son in the garden shed.

“I had a basket case of an old Harley Shovelhead that had been in the shed for 18 years, and a couple of years ago he asked me ‘what are you doing with that bike? Can we build it together if I pay for it all?’ I said ‘fair enough’, so we built it in the shed one winter.

“He’d been riding a Yamaha trike on a car licence, so we put a truck back axle from America on the Harley and turned it into a trike.”

As for one day leaving Ben the Duo-Glide, Bob may take a little more persuading yet.

“It’s a dodgy situation riding bikes these days,” he says. “I don’t want to sound like my dad, but I’m lucky, I’ve been on these bikes since the 1960s, and have done some stupid things over the years and only got away with it because there was not the traffic there is now.

“You’d run out of road and go wide on bends, but in this day and age there would probably be something coming the other way and it would wipe me out. I would hate him to be on a bike now. Car drivers don’t understand these days, because most of them haven’t ridden bikes.”

Whatever the future holds for the Harley, Bob plans to keep living his boyhood dream for as long as he can.