As a teenager, Dick Lingley only had eyes for one bike – the “iconic” Kawasaki Z900.

He would ride his beloved Chopper pushbike from Stevenage to Hitchin and hang about outside Jimmy Lane’s bike shop, where bikers would meet on an assortment of British and Japanese machines.

“The British bikes would all be leaking oil, but there were a couple of Zeds there, and it was like seeing a spacecraft,” he remembers. “I thought ‘if ever I have a bike, it will be that – you will be mine’.”

Fast forward nearly 20 years, and Dick has taken his three daughters – he now has five – for a day out at Pevensey Bay in Sussex, a place with memories from his own childhood.

“It took me back, because my parents used to take me there as a kid,” he says. “They’d go to the pub or whatever, and I’d go sea fishing – I never caught anything.

“I spotted this motorbike shop, so sent the kids off to get an ice cream while I had a look in there.

“Then I saw the Zed”

“There was all sorts of other stuff in there, and then I saw the Zed. It was black, which I thought was sacrilege, and the bloke said ‘you can have it for about £1,500’.

“I said ‘I wish, I’m going on holiday next week, I’ll get shot’. But then I got home, thought about it, phoned him up and said ‘can I put a deposit on my card now?’ A week later I went down and got it, but we didn’t go on holiday…”

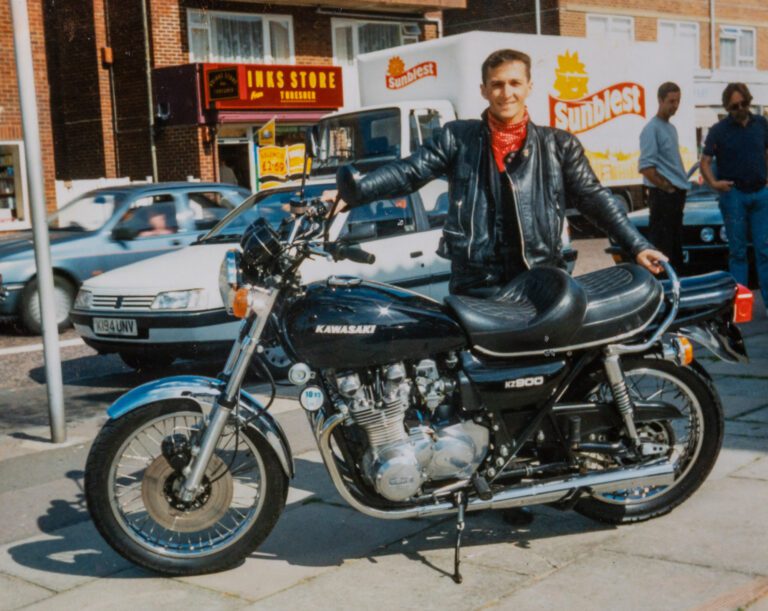

That was the summer of 1993, and it was the fulfilment of a long-held dream for a Dick, who cut his teeth riding Raleigh Runabouts on the fields near his home aged nine.

“It’s just an iconic bike,” he says. “People see them as art now, but they sound good and they go. I just love it to bits, more than anything, and I’d never get rid of it.”

Dick’s bike is a 1976 KZ900 A4, built in Japan the previous year and exported to Seattle in the US before making its way to the UK and, ultimately, the Motorcycle World bike shop in Pevensey.

Kawasaki was in the process of developing a 750cc across-the-frame four-cylinder, four-stroke bike when Honda beat them to the punch in 1968 with the game-changing CB750 four.

Project ‘New York Steak’

It prompted a delay to the launch of what was known as project ‘New York Steak’ while engineers worked on a way to beat the spectacular new Honda.

The answer was to bore out the engine to 903cc, and the Z1 – as it was known at the time – was born in 1972, the first large-capacity Japanese four-cylinder to use a double-overhead-camshaft on a production motorcycle.

Nothing like it had ever been seen before and it took the biking world by storm, outperforming the Honda with a top speed of up to 132mph and setting the 24-hour endurance record on the banked Daytona racetrack.

It was renamed in 1976 as the Z900 and KZ900 in the US, where it was often fitted with a king and queen seat like Dick’s and slightly higher handlebars.

“It was the superbike on the planet at the time,” he says, “far superior to anything else when they came out, and they still are. Riding it was a smile from ear to ear, but you did have to ride it.

“On the earlier bikes, allegedly, if you went at certain speeds you could feel the frame distort, but they strengthened it for the A4.

“They also realised it didn’t stop that well, so stuck another disc on the front. This one only had one disc, but it had the lugs for another one so I stuck one on.”

Passion for bikes

To understand Dick’s passion for bikes, we need to go back to his formative years and his exploits on the Raleigh Runabout.

“Once that’s in your blood it stays there, and you can’t explain it,” he says. “All these idiots on drugs and things, they don’t understand what a fantastic buzz you get from riding a bike.”

Always a hyperactive worker, Dick did a paper round and decorated people’s homes from as young as 10, saving up enough to buy the Chopper.

“My mate had a Claude Butler lightweight, a beautiful bike, and they all used to take the piss and laugh at me,” he smiles. “‘It’s like riding a bedstead’ – it was so heavy. But I absolutely loved it – it made me smile and they all secretly wanted one too.”

When he was still 15, and an apprentice at the British Aircraft Corporation (later British Aerospace), his father told him about a Yamaha FS1-E for sale.

“He said ‘one of those bloody Fizzy bikes you want, my friend’s son’s selling it’, so I went to see him, and I had it straight away,” he remembers. “I think it was about £110, so I got £15 for the Chopper and bought the Fiz. It had probably done about 80 miles.”

A year later he bought a Honda CD175 sloper, before the kickstart went and he upgraded to a brand new Suzuki GT250A in 1976, on which he passed his test.

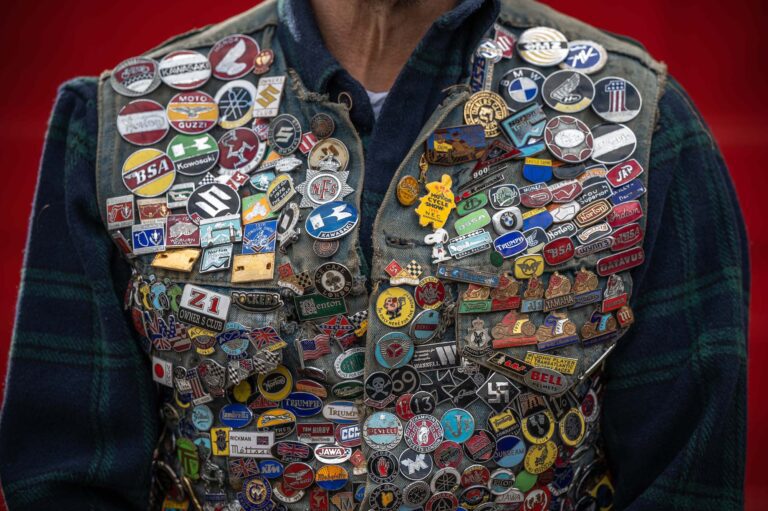

Levi denim jacket

By now, Dick had acquired the Levi denim jacket with cut-off sleeves that he’s wearing for our photoshoot, adorned with countless metal motorcycle badges acquired over the years from shops and shows.

“It probably weighed about one-and-a-half stone back in the day, and I remember wearing it when I came off the 250 on some ice,” he says.

“There were sparks flying along the road from all the badges. I went back there about a month later and must have picked up about 20 badges off the road.”

The GT250 was then replaced by a black Suzuki GT550 before Dick got a car – a Ford Capri 1600GT – and marriage, mortgages, work and children saw motorbikes take a back seat.

After his apprenticeship, Dick worked – and still works – as an electronics engineer, kitting out police vehicles with ANPR camera tech, and travelling all over the world on special assignments.

“At one point we were fitting long-range cameras, up to 50km, for the military in Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon, getting shot at,” he says. “I enjoyed it, and we actually built one for the president of Kurdistan and fitted it onto the back of his Ford heavy duty 350 truck. I don’t think they even knew how to turn it on!”

Irresistible lure

After the biking hiatus came 1993 and that fateful trip to Pevensey Bay, when Dick couldn’t resist the lure of the bike he had lusted after for years.

Dick, now 64, rode the bike for about five years, retaining the American-style blue jewel in the rear light and the non-original black paintwork.

“I went over to the Netherlands on it with some mates, and we went all over,” he says. “We stayed in a place up near Mont Blanc and did Switzerland, Belgium and Germany.

“We went round the Spa and Nurburgring circuits, and I thought I was really going for it but then saw some of my mates going round scratching their ears on the ground – on the video it looked like I was almost standing up!

“I got it up to 120, but the needle was rattling a bit and the tacho cable actually broke. I gave it a caning that day. It was perfect.”

In 1998, however, he bought a brand new 1200cc Suzuki Bandit, and he suddenly had “another bike to play with, and that was super quick”.

The Z-bike is shelved

“The Zed was kind of shelved, but I wanted to strip everything down and do a nut and bolt job on it,” he adds, the Kawasaki initially stored in a friend’s garage.

“I used to go up there sometimes and there’d be a foot of water on the floor; I thought ‘I can’t have this’, so I moved it into one of my work units and then to another house we bought which had a double garage.

“When we moved to the new house, I took the tank and panels off and sent them off to Dream Machine to be painted in the proper green. I just love that colour scheme.

“I sold the Jardine exhausts on eBay for about £50, and in 2004 bought the correct Kawasaki exhaust system from Z-Power.

“They said to me they could only put the order in when they get so many, and I’d probably get one of the last sets because they’re not making them anymore. Then he phoned back and said ‘I’m really sorry, the price has doubled’. It went from £375 to £800, and cost me a grand with all the bolts and everything.

“But it’s a proper Kawasaki exhaust, and these days you can only get replicas.”

But then work ground to a halt.

“Lost heart”

“Everywhere I’ve been it’s just been there – ‘I’m going to do you up’, but I sort of lost heart in doing it,” he admits, no doubt partly because he had yet another new bike to play with in the shape of a 2004 Yamaha Warrior.

“When the exhausts arrived, I wanted to put them on but I had cars going in and out of the garage and I didn’t want them to get dinged and damaged, so they’ve been up in the loft ever since.

“I used to dream about mice and rats going in there and nesting. We found an old teddy bear of my wife Tracey’s from when she was a kid, and the mice had got at that.

“I hope my exhausts are all right!”

Similarly, the tank and body panels remained in their bubble wrap in Dick’s bedroom for the best part of two decades.

“But then you phoned me up,” he smiles, “and made me get a wiggle on after 20 years.”

The exhausts, tank and panels were rapidly exhumed from their resting places and fitted to the frame, along with a re-covered 1976 seat to replace the “horrible” king and queen version.

“All I’ve got left to do is refurbish the front forks and the brake callipers, and it’ll be black on the road,” he says.

“I’m going to be paranoid”

“I’m going to love it, but I’m going to be paranoid about being taken out on the road by someone, or even dropping it on the exhaust. I don’t care about me – well, I do – but I care more about the bike.

“And you can’t leave it anywhere, because it’ll be gone. But I’ll go to shows and things when the weather’s good, like the Silver Ball Cafe near Royston where people go for meet ups on a Sunday.”

Tracey, who enjoys the armchair ride of the Warrior, will go out on the Zed with Dick, and will “love it”, he says.

But his five daughters are less keen these days.

“They used to come out with me, but now they hate me going out,” he adds. “‘Dad, sell the Bandit! They think it’s too fast, but they don’t seem to have a problem with the Warrior, which is super powerful.”

We head out to Dick’s carpeted garage, where the Kawasaki lives with its own Mini-Me, a kit that Dick made when he first bought the bike, complete with matching Letraset number plate.

It’s clear that he doesn’t like to part with things – there are the antique bottles collected over many years, along with about 150 Airfix aeroplanes, cars and bikes in boxes in the loft above – all remnants of his childhood bedroom.

“I love coming in here and just smelling the bikes and doing bits of work on them,” he says, “it doesn’t even matter if I don’t ride them much.”

But after 25 years off the road, this legendary ‘70s superbike is once again ready to roar – and there’s no chance it will ever be sold.