Dave Cornish’s Ducati 900SS is the bike that keeps coming back.

The former Enduro and Supermoto racer was just 19 when he first bought the iconic machine in 1981, since when he’s sold and bought it back twice.

After selling it for the second time in 1987, Dave was finally reunited with the bike in the summer of 2019.

“It’s not going anywhere this time – it’s staying,” he says. “It’s got so many memories, and I never would have got another chance to buy that bike, so I had to do it.”

Rollercoaster ride with the Ducati 900SS

The past 40 years have been a rollercoaster ride for the Ducati, taking in crashes, catastrophic engine failures, a honeymoon to Silverstone, and devastating tragedy.

All this, and more, comes pouring out as we chat in Dave’s garden, a few minutes drive from the east Norfolk coast.

There’s his unconventional route into biking, his lust for racing ended by a near-fatal accident, and helping his son Lewis fulfill his own Supermoto dreams.

Born in Rotherham, Dave moved with his publican parents to Norfolk, where they had enjoyed boating holidays on the Broads, in the early 1970s.

In a bid to steer him away from two wheels, his mother gave him a car when he was just 15.

“There’s an anti-motorbike history in my family,” he says. “Unfortunately, before I was born one of my relations was killed on a bike, so, no bikes…

“My mother had a mark two Cortina and she somehow put it through the petrol pumps in a local garage – petrol everywhere – and afterwards it sat there rotting away.

“She said ‘you can have that Cortina, but you’re not having a bike’.”

After “bodging it up”, Dave drove it around the fields near his home, but sold it for £150 to the foreman at a local haulage contractor where he was doing some work as a mechanic.

“I just went out and bought a Fizzy (Yamaha FS1E),” he laughs. “She was absolutely furious. She expected me to wait two years to drive the car on the road. No.”

With that parental hurdle overcome, Dave passed his bike test to rid himself of L-plates and explored the Norfolk countryside on two wheels, often relying on his father to collect him from various breakdowns.

“I’d phone my dad up, ‘I’ve broken down’,” he says, remembering a large amount of freedom with his parents both working evenings in the pub.

“He’d say ‘yeah, the pub shuts at 11 o’clock, by the time I’ve sorted myself out, it might be 12 o’clock, where are you?’ That happened several times.”

Late night rescue missions

One Sunday morning in the pub, Dave’s father – no doubt fed up with his late-night rescue missions – called him through to see a customer.

“It was a guy who lives in the village, Patrick Atkinson, who used to have Atkinson’s Honda, and we got in his Volvo and went down to his showroom,” he remembers.

“There were three brand new CB50s sitting there, one of each colour and I thought ‘ah, my dad’s bought me a bike, excellent, I’ll have that one’.

“All right, it was restricted, but it’s a free bike and it’s brand new. I signed on the dotted line, not knowing that I’d got to pay £7.50 a week or something, nearly half my bloody wages!”

Dave would ride the Honda to Norwich City College, where he was studying to be a mechanic, and one morning in 1978 “this bike came past me, a two stroke, in a cloud of smoke”.

“I got to college and it was somebody I used to go to school with on a Malaguti, obviously unrestricted, and I bought that off him,” he adds.

“That didn’t last very long, it got written off when someone came through a red light…”

Love of Italian bikes

The Malaguti sparked a love of Italian bikes, but Dave’s next bike was a Honda TL125, before realising competition bikes were not really suited to road use.

“The fuel tank held as much as that cup,” he says, pointing to my coffee cup. “I went up to Sheffield to see my grandparents and had to take fuel cans with me, and it was so slow.

“While I was up there I went into a bike shop looking at 400s, and I actually got offered about £20 more than I paid for this bike on a trade in, so I came away with an RD400.”

But Dave, still just 17 and still hankering after an Italian bike, had seen a brand new Moto Guzzi 850 Le Mans in a local dealership that looked after the police Guzzis.

“It had been there ever since I could remember,” he says. “I went in one day and the price had been reduced to £2,250 or something.

“It was a lot of money in those days, and I raided every account I had, and borrowed, and bought it. It’s been Italian bikes from there on really.”

At the tail end of 1980, Dave returned to Sheffield to buy the one-year-old, race-bred Ducati 900SS that would be in and out of his life for 40 years.

“Mike Hailwood had just won the TT a couple of years before on one, so I thought ‘it’s got to be the bike to have’,” he says.

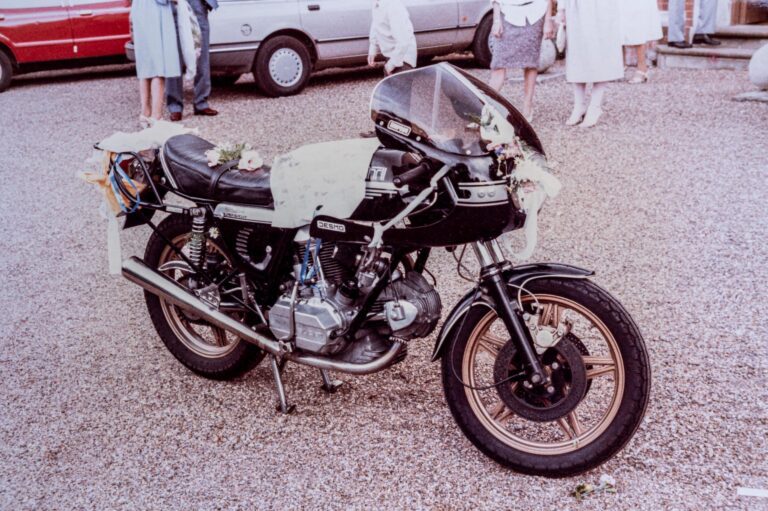

Even when standing still, the Ducati looks purposeful, aggressive, like its front wheel is trying to escape up the road at a rate of knots.

Motorcycling in the raw

To ride one is to experience motorcycling in the raw.

“It’s a handful to ride,” he says. “I was a bit concerned. All right, I’d had a Guzzi and other bikes, but it was a bit more hardcore, open carbs, open exhaust, the riding position is pretty extreme, and there’s only a kickstart on it so you’ve got to man up.

“It’s long, it’s stretched out, there’s nothing on it that doesn’t need to be on it. It’s just meant for riding fast in a straight line, or going round fast corners – it’s not meant for traffic or slow corners.

“It’s not that practical, but once you are on the open road and at speed it’s reasonably comfortable.

“I rode it home from Sheffield and was just in love with it.”

Dave hadn’t owned the bike long when he came off it one lunchtime.

“I found out later it was because it had the wrong exhausts on,” he says. “One of the header pipes was incorrect and it grounded out and just lifted the front wheel off the ground.”

Frank, a friend from New Zealand, had been bugging him to sell him the bike and, after finding parts from Italy incredibly hard to come by, and prohibitively expensive, Dave finally relented.

“He bought the bike and it needed a rear tyre, so I said to him ‘I’ve already ordered one from ATS, I’ll get it for you on Monday’,” recalls Dave.

He never saw Frank again.

“I went to pick the tyre up, and the ATS guy said ‘what’s this off then, it’s unusual?’” he says. “I said ‘it’s off a Ducati’, and he went ‘ah, there was a guy killed on the seafront on a Ducati this morning’.

“My heart stopped”

“My heart stopped, basically. No, it can’t be. Ducatis in 1980 were rare, and it was him. I was only 18 or 19 at the time, and I was devastated.”

The following spring, a friend of Frank’s came over from New Zealand, and got in touch with Dave.

“He found out that the bike was kept at a coachworks on the seafront in Yarmouth,” he says. “We went there to look at it, and it was a mess. This guy said ‘I’m going to get that back off the insurance’. The next thing I know, months later, and wow, he’s done it up.

“When he went back to New Zealand, he asked me if I wanted to buy it back. It was a no brainer, but it was a bit of a strange feeling, knowing that Frank had been killed on it.”

The Ducati became Dave’s main form of transport, and took him and new wife Julia on their honeymoon in 1984.

“After the reception, we got on the bike to head off to Silverstone for the following day’s Grand Prix,” he says. “They had rammed confetti down the exhaust, and it didn’t want to start. When it did start, there was a massive cloud of confetti.

“We spent our wedding night at Silverstone, and then went to Derbyshire and Yorkshire for a few days.”

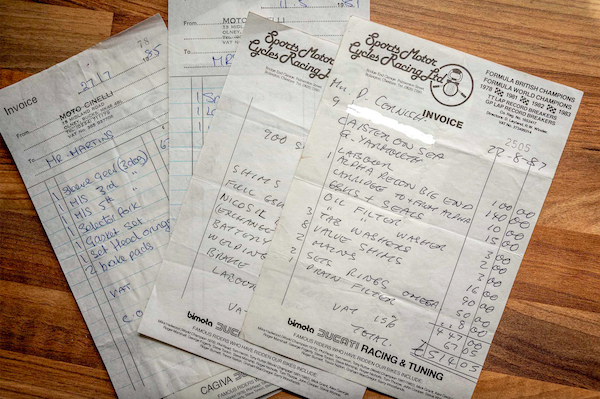

Although he concedes the Ducati is “not a touring bike”, it made regular trips up north to visit family, suffering catastrophic engine failure more than once.

“It usually happened on the way to or back from Yorkshire,” says Dave, ruefully. “I had a crankshaft let go on the Swaffham bypass on the way home, at quite a speed.

“By the time I had pulled the clutch in there was a big chunk of rubber on the road. It did another one at Sutton Bridge on the way to Yorkshire.

Hearing a death rattle

“The third time it went was at Donington Park in 1988. I was doing an Italian track day and I heard that death rattle and thought ‘oh no’.

“I pulled in and Steve Wynne from Sports Motorcycles, who built Mike Hailwood’s Ducatis, was there. I said ‘I know what it is, I’ve heard it several times’. He gave me the tools and I took the engine out, gave it to him, and he took it away. We called the RAC just to take the chassis home. He fixed it for me and I put the engine back in.”

But the cost of repairing these regular breakdowns had become too much.

“I just thought, I’ve seen this happen three times and I was not on good money at all,” says Dave.

“I had a mortgage, they were tough times, and every penny you’ve got was accounted for. I just didn’t want to face that again.”

So he sold the bike to Geoff Tubby, a colleague at the Great Yarmouth-based truck garage where he worked.

“He was older than me and he could never start it,” he laughs. “Instead of getting on my bike or getting in my car and tearing off in the evenings, I would wait around, mainly just to laugh at him.

“I’d go out there and start it straight away. He didn’t have the power or the technique really.”

By then, Dave had been racing big, single cylinder dirt bikes for nearly 10 years, “and they are a nightmare to start, so this twin cylinder was relatively easy for me”.

Nevertheless, Geoff did manage a big trip to Italy on the bike, plus several trips to Scotland, before parking the bike up in his barn in 1995.

In hibernation for almost 25 years

It didn’t move for nearly 25 years.

Unlike the Ducati, Dave had been far from idle in the intervening years, competing in Enduro racing and Supermoto for more than two decades, bringing up two children, working in Libya for seven years, and editing Supermoto magazine and Trail Bike magazine.

His racing career started when he was 18 and “earning peanuts” as an apprentice mechanic.

“I bumped into an old school friend who said he was going to do Enduro,” he says. “I looked into it and you can race all day for a £15 entry fee, you just need a bike.

“I bought a (Yamaha) DT175 trail bike to get me started and after a year or so I decided I liked it, so I swapped a Laverda Jota for a brand new Moto-Gori 250 Enduro bike and an old Morini 350.

“I was convinced I was not British champion because I didn’t have the correct bike. Needless to say, I got the correct bike and I was still not British champion.”

Dave may have enjoyed the rough and tumble of off-road racing, but his body did not.

Dave’s experienced some bad accidents

“I had some bad accidents,” he says. “I was getting so beat up, absolutely mangled really and it’s constant. I had a reconstruction on my left knee, and this one needs one (pointing to his right knee).”

But while he stopped Enduro racing aged about 30, he merely swapped it for Supermoto, which is predominantly raced on tarmac but still maintains an element of off-road.

It proved no less dangerous.

“I had a serious, serious accident, and lost three or four days with a head injury,” he says. “I woke up in a hospital in Bangor, in Wales, with my wife and my mum there.

“I was basically told ‘don’t bang your head again’, so that was time to quit.”

Then 41, he was also forced to leave his job working six weeks on, six weeks off, in the deserts of Libya, an environment he describes as “tough as hell”.

Fortunately, he was able to fall back on his work as a freelance motorcycle journalist, writing full time while he recuperated.

“When getting over my injuries, it gave me some focus and, because I couldn’t remember anything, I think doing the research and writing mentally helped me with my memory,” he adds.

His route into journalism had been characteristically eventful.

It stemmed from working as a support driver and mechanic for Dust Trails, an ambitious and ultimately doomed expedition for escorted bikers to ride through Africa.

“It was a pretty eventful eight weeks, driving through Europe to Genoa then across on a 30-hour crossing to Tunis, then onto Algeria and down to Tamanrasset, through the Sahara and Hoggar mountains,” he says.

Trip goes south

“Then it all went wrong. The journalist with the party was violently ill – he wouldn’t eat or drink.

“We just saw him go downhill quickly. My friend was telling me about when he was in Nigeria, on an overland trip, a teenage girl died and they had to bury her in the jungle and then go and tell the authorities.

“I said I don’t mind digging the hole, I might even put him in it. We were drawing lots. Thankfully he slowly got better, and I actually flew home with him.”

Dave had kept a rudimentary diary of the trip, and the journalist asked him if he could borrow it to remind him of the two weeks he had lost through illness.

“He then asked me if I wanted to go on an off-road bike test in Derbyshire, so I wrote a couple of hundred words on that,” he says, with things then escalating quickly.

“Within a few years I’m an editor (bloody stressful) and then publishing editor (Jesus Christ, early grave here!).”

He called time on his journalism career and has spent the past 12 years or so working in the offshore industry.

Supermoto son

There’s also been the small matter of supporting Lewis’s Supermoto career, which has taken in Europe, the USA and Asia over the past decade.

Lewis and his older sister, Francesca, were both riding bikes from the age of four.

“He always looked up to his big sister, so when he saw her riding a motorbike, he wanted to do it,” he remembers.

“When he was about four, I told him ‘you can’t even ride a bicycle – when you can without trainer wheels, maybe’. He came in an hour later and said ‘I want to ride a motorbike’.

“‘I’ve told you, when you can ride a bicycle’. ‘I can’, he said. He’d bent the trainer wheels up somehow and he was cycling round – I thought ‘here we go, that’s determination’.”

Lewis has since been British Supermoto champion four times and now lives and races successfully in Asia.

Back to 2019, and Geoff contacts Dave out of the blue. He is selling his farmhouse and needs a new home for the Ducati 900SS that has been stored in his barn for the best part of 25 years.

Dave and Ducati 900SS reunited

“I had moved house, moved jobs and lost touch with him, but he found me and said ‘do you want to buy your bike back?’” says Dave. “I’d sold him a number of bikes over the years, so asked him ‘which one’?

“I was hoping he was going to say this one.”

Dave wasn’t surprised that Geoff still owned the Ducati: “I worked with him for six or seven years and I just knew what he was like – a real hoarder.

“And everything’s got to be just so, and if it’s not just so, he doesn’t use it. Hence, the bike wasn’t perfect, and he put it to one side.”

Buying the bike back was an easy decision, and Julia was behind him all the way.

“Julia was happy to see it back,” he says. “She said ‘you can’t not buy it can you?’ I guess it’s like reliving your youth. It’s the fact that it’s got so many memories – we got married, blowing the engine at Donington, crashing it a few times.”

When Dave got the bike home, it was pretty rough, and missing a battery and a few other bits.

“I got it in the workshop, took the spark plugs out and put a moped battery on,” he says. “I got a spark, put some oil down the bores, turned it over and it seemed fine. I put the plugs back in, stripped the carbs, which looked fairly clean, and put some fresh fuel in.

“On its first kick since 1995, it started up in a big cloud of smoke.”

There was much work to be done, however, before the bike could be ridden on the road.

“Everything needs doing”

“I couldn’t ride it – the tyres looked like concrete apart from anything else,” he adds. “I spent most of the morning cleaning it. It was ‘oh God, everything needs doing’. There was aluminium corrosion, ferrous components corrosion, the rubber was perished and split.”

Dave stripped the bike down, restored the frame himself and sent the bodywork away to be brought back to its best.

The engine and gearbox were rebuilt by Carl Harrison, who had worked on the bike back in the ‘80s, with aluminium welding undertaken by Nigel at Qualitig and the electrics brought back up to scratch by Gary Button at Yarmouth Rewinds.

David Blanks at East Bilney Coachworks and Aerocoat were entrusted with paintwork and powder-coating respectively, with the petrol tank saved despite having suffered extensive damage which had been repaired with plenty of filler.

“When David showed me the results of his and his workmates’ handiwork, it was just top quality with an absolutely amazing depth of shine which is way beyond what it was in 1979,” says Dave.

Parts came from as far away as Syd’s Cycles in Florida to Ducati Paddy and Mdina Italia in the UK, while the tyres – a modern version of the original Pirelli Phantoms – were supplied by Dave Clarke Racing.

We first met Dave in August 2020, when parts of the Ducati were scattered in workshops across the UK.

900SS comes roaring back to life

Eight months later, on a chilly April day, the bike is finally back in one piece and Dave is back in his 15-year-old racing leathers, cajoling the SS into roaring life.

We follow him to The Boathouse pub, on the banks of Ormesby Broad, where Dave lived with his parents when he first bought the Ducati.

“I was living here when I first met Julia so there are a lot of memories, and it’s like everything has come full circle,” he says, parking the bike by the windswept lake where he would hire out boats as a teenager.

“When it first started up, it was very emotional, and it feels really good to get back on it. It’s still not perfect and I want to finish it off – both seats (single and double) still need re-covering.”

These days, the values of the 900SS vary widely, depending on when they were built.

Early racer replicas have more than doubled in price since 2018, and Dave says one recently sold for £175,000, while later production bikes like his own black and gold model can fetch from £25,000 and up.

“I went in a showroom of an Italian bike specialist last year, and they had a black and gold Ducati, pride of place, for £25,000,” he says. “The one behind it was a year older, maybe two years older, and that was nearly £50,000.

“I told him I’d just bought one as a project, and he offered me £15,000 for it as it was. But it’s not about money and, ultimately, I’m not going to sell it anyway.

“It’s had a hard life, under me for sure, and this is probably just a nice little safe retirement for it, the occasional ride out on sunny days and maybe to a local show.”

One day, this precious Italian thoroughbred will pass to Lewis, but for now Dave will enjoy rolling back the years on the bike that keeps coming home – this time, for good.