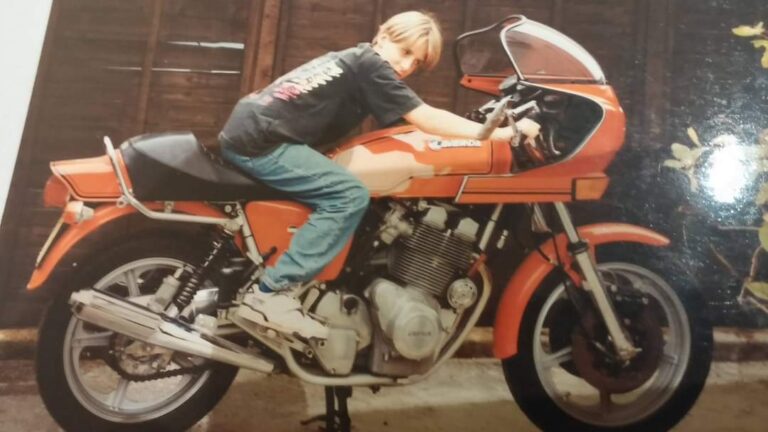

Colin Shillings fell in love with motorbikes as a teenager in Cyprus, and became besotted with the Lamborghini of motorcycles – the Italian Laverda Jota – in Lincolnshire.

He’s lived in Malaysia for the past 30 years, but this well-travelled engineer tries to return to the UK at least once a year to see family and ride the beloved Jota he has owned since 1984.

In love with the bike

“I’m absolutely in love with the bike,” he says, speaking on one of his short trips from his permanent home in Kuala Lumpur. “It means everything to me, and my mates in Malaysia are sick of me talking about it – every time we meet for a ride I show photos of it to any new group members.

“They keep saying ‘well bring the bloody thing over then’, and I always say I’m planning to, but no-one there can help me maintain it.”

Colin’s father was in the Royal Air Force and, after moving from Ipswich to RAF Scampton in Lincolnshire, the family decamped to Cyprus in 1969.

“That’s when I started to get a love for bikes,” he says. “In the main city in Limassol, where us kids would sneak off to, there were a few bike and car dealers and I always remember seeing these bikes in the shop.

“The window was off the ground and there’s this new BSA Rocket 3 looking at me and I thought it was awesome.

“I had one quick spin on somebody’s scrambler over there, and it sort of hooked me, but I couldn’t get one.

“When I knew we were coming back to the UK in 1972 I started looking forward to getting one, but they changed the licensing rules that year. I was 16 so I had to wait another year until I could get a decent sized bike.”

In the meantime, he rode a Raleigh Automatic moped back and forth to work as an apprentice design engineer at Ruston Gas Turbines, now Siemens, in Lincoln.

A year of waiting

“It was basically a year of waiting,” says Colin, who moved up to a Yamaha YDS7, a two-stroke parallel twin, when he turned 17. “I wish I’d kept it, because good ones are now quite sought after.

“It was just great on this big bike, so powerful compared to a 50cc. As soon as I passed my test I got a ‘68 Triumph Bonneville 650, which I loved, a great bike.”

Nonetheless, the Bonny was replaced by a 1972 Norton Commando 850.

“It was a red roadster, in pristine condition, and beautiful,” he says. “I paid £600 I think, and got my dad to sign the loan agreement.”

But in 1976, Colin was deeply wounded when the Norton was stolen while he was at the cinema in Lincoln.

“We used to chain the bikes to these posts, and there was a gang going round then breaking bikes down apparently,” he remembers.

“Years later the cops notified me that they’d found the seat in America. It was really sad, because I’d never have got rid of that.

Loss of Norton “a shock”

“Losing the Norton was a shock for me, it pissed me off, and by that time I was settling down so my priorities changed as well.

“I never really thought about buying another decent bike until this Laverda came up for sale. I had other bikes in between, but nothing special.”

Colin had long held an interest in the bikes made in Breganze in north east Italy, and he had the chance to observe them up close when Lincoln businessman Harold Overton and his son appeared on the scene with two Laverdas in the mid ‘70s.

“I believe they had the first Laverdas in town, although they were 3CEs or 3CLs, the machines that the Jota is based on,” he says. “They were lucky, because they were expensive bikes then, probably the most expensive bike you could buy.

“They ran an agricultural machinery business, which is probably why they liked the Laverdas, which some say sound like a tractor.”

Laverda started out as agricultural engine manufacturers, diversifying into motorcycles in 1949, with the 3C triple range introduced in 1973.

Jota born in Herefordshire

But the Jota was born in Herefordshire, not Breganze, when Laverda’s UK importers – brothers Roger and Richard Slater – decided to tune the 3CL to go racing.

The bike’s double-overhead cam, aircooled, 981cc engine was given bigger valves, high-lift camshafts, and high-compression pistons, boosting output from 85 to 90hp at 8,000rpm.

Top speed was now 146mph, making the newly-christened Jota – a Spanish three-step dance – the fastest production road bike in the world when it went on sale to the public.

Its 180-degree crankshaft arrangement with two up, one down piston stroke gave the bike a unique sound.

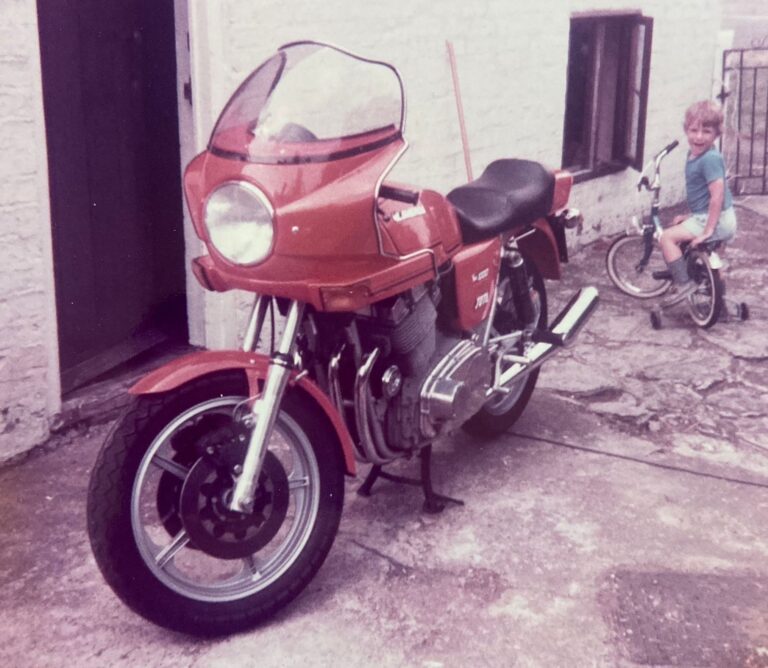

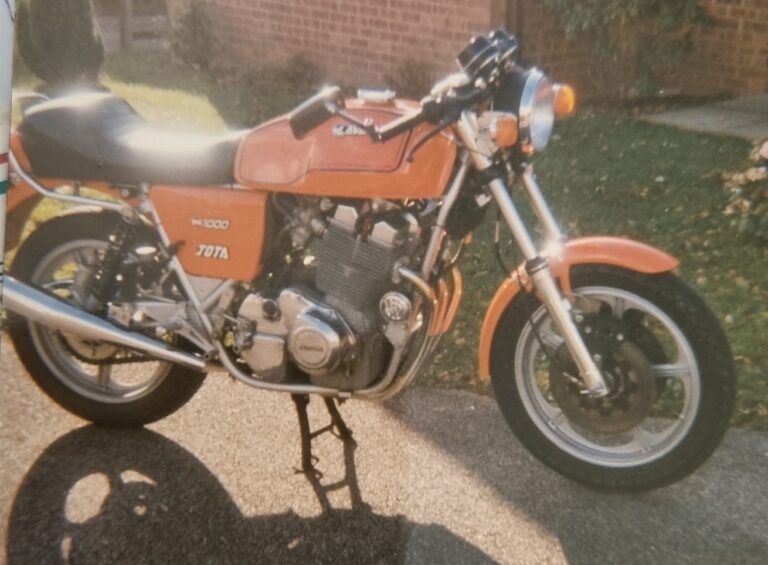

Laverda was so impressed they took on production of the Jota for markets around the world, switching to a more reliable 120-degree crankshaft, but Colin’s 1981 bike is one of the UK-born Slater Bros machines, adapted by the brothers from a 3C.

“I’d always wanted to have a Laverda, but I could never previously afford one,” he says, “but now I could.

“I think I asked Slater Bros to let me know if any came up for sale, and one of their staff phoned me up and pointed me in the direction of this one.”

Colin paid £3,000 for the orange and silver Jota with a Slater-fitted fairing, and vividly remembers riding it home from Northampton.

“Fantastic” first ride

“The first ride was just fantastic,” he says. “I think I went a maximum of about 60mph, but I did accelerate a lot and could feel the power – it was really exciting. It was like nothing I’d ever ridden before.

“Make no mistake though, it’s a beast to ride, it really is. It’s got massive torque for an old bike like that, and these bikes rev above the red line, shown as between 6,500 and 7,500 on the clock, but it’s said you can rev it right up to 10,000.

“The main torque is at 7-8000 and I’m not joking, this feels like it will lift the front wheel off the ground at those sorts of revs, even in third gear.”

The Laverda took a bit of getting used to, so different was it in character to Colin’s previous bikes.

“To start with, it did feel clunky because I’d never ridden one before, and getting it into gear was an art sometimes,” he adds.

“I’m not sure if that’s to do with the way it fires, or the change of gear linkage from right to left that Slater did.

“It’s awesome”

“But it’s awesome, and it handles so much better than any Japanese bike I’ve ridden and better than the Commando. This was a different level of handling – it just felt like you put it on a line and it stays on a line, it’s incredible.

“A lot of people say you need to counter steer it, which you do, but only if you’re really hammering it.”

In truth, the only time the Jota has been truly hammered is when Colin took it round the Cadwell Park race track.

“It was just great,” he says. “It’s a fairly short straight, but I got it up to 120mph, which is the fastest I’ve been, and I’ll admit I get a bit scared when it gets to that.

“I had a really nasty accident on a bike once – I was in hospital for ages, and my hand is still distorted from it, so when I start going too fast I remember that time in hospital and slow down a bit.”

Over the years, there have been few issues with the bike, but Colin did take the bike back to Slaters for some pre-leaded petrol work.

“I vaguely recall they did something with the valves and seats and changed the valve springs to stronger ones,” he says.

“I think the valve spring change was something they did as a result of their experience with power loss after short periods of racing the bikes. In fact, when they showed me some Jota valves there seemed to be evidence that they may have actually touched each other – maybe after a missed gear?”

Jota purely for pleasure

The Jota was used purely for pleasure, never for commuting, and only on dry days – “it’s never been in the salt”.

From Lincoln, Colin took the Laverda to the Netherlands, where he had landed a job, before it came back to the UK in a van about a year later, this time to Nuneaton.

“I then started a company in South Wales, near Port Talbot, with some other guys, and rode the bike down there,” he says. “We were manufacturing products for the oil and gas industry, and I put every penny I had into it, except the bike.”

Colin first started visiting Malaysia for work in 1989, initially working for a Lincoln-based Engineering Company and then the Wales-based company.

Since 2001, he has been working in technical business development for a large multinational engineering company.

Over the past three decades, the Laverda has remained in Lincolnshire, looked after by a combination of Colin’s son Luke, Luke’s uncle, and Phil at Italia Moto, who has now retired but still helps to get the bike up and running when needed.

Covid interruptions

Luke starts up the old bike and takes it for an occasional spin to keep it ticking over and, apart from an interval of a few years because of Covid-19 travel restrictions, Colin tries to take the Jota out on rides when he returns to the UK – but today is the first time since August 2019.

“I get it out, start it up and take it somewhere,” he says. “The last time was in 2019, when I went off to Willingham Woods, which has become a really popular place for bikers on Wednesdays and Sundays.

“When you’re getting it back on the road every year, quite often something will happen – it will start spluttering, the carb might need cleaning or something. But it was running really well, so I had decided to risk riding the 30 miles or so.

“I rocked up there on a Wednesday afternoon, before the crowds arrived in the evening, and there were five or six other bikes.

“We were having a cup of tea in the cafe when bikes started coming, and I saw this really old Matchless 350, and something about it looked familiar.

“He got off it and started looking at the Jota, came over and said ‘you’re Colin Shillings aren’t you?’ I hadn’t seen that guy, John Clixby, for 35 years, and he still had the Matchless he had at the time.

“We went from there to his house close to Cadwell Park.”

Since 2019, the bike has seen very little action and, while it looks remarkably clean and tidy to us, Colin is a harsh critic.

“It has got one or two little rusty bits, and I’m disappointed that it’s got even one speck of rust on it,” he says, “but a bike of that age is going to have that I guess.

“It’s purely because of Covid and the fact that it’s been standing there for four years.”

Legendary Italian superbike

Nevertheless, the Jota fires up and we head off for our photoshoot, a local biker who owns a Harris Magnum (read more) stopping by to admire this legendary Italian superbike.

“I’m in love with this bike, right?” says Colin, “and it’s never come into my mind to sell it. I will never willingly let it go, and it’s in the will for Luke. But whatever happens to it, I want it to be original – I don’t want to change anything.

“There’s just something about it – no electronics, no rider assistance, no aids. When I ride it now I have to remember it’s 40 years old, and it doesn’t just stop like the Ducati XDiavel S I ride in Malaysia.”

Most weekends in Kuala Lumpur, Colin and his mates ride the 100 kilometre round trip out to the mountains, winding up through “these lovely bendy roads” to enjoy a coffee at the top of the range.

“When I’m on my Ducati, every time I picture myself doing it on the Laverda,” he says.

Maybe he should take the bike to Malaysia after all…