Stunt Riders

The greatest stuntmen in the world

Stunt Riders

The greatest stuntmen in the world

The Pioneers of Motorbike Stunts

The history of two-wheeled stunts revved up way back in the 1800s. Daniel Canary, a telegraph messenger from Connecticut, gained fame thanks to the tricks he was performing on a Penny-Farthing style bicycle.

Shortly after the invention of the modern safety bicycle he was credited with performing the first wheelie. The name of the person to perform the first wheelie on a motorcycle has been lost to the ages, although given the quality of the roads and the epic nature of their journeys, it’s possible that early biking legends like Erwin Baker did a wheelie at some point without feeling the need to mention it.

Motorcycle stunt riding quickly became part of travelling carnivals, with portable tracks becoming regular sights. In 1915 someone had the bright idea to stand the tracks vertically, in what were originally called silodromes but soon became known as the Wall of Death. Bikers start at the bottom of the drum and, building up speed, are able to drive horizontally around the inside of the drum. These Walls of Death were an instant hit, and by their heyday in the 1930s there were over one hundred in the US, in travelling shows or at fairgrounds.

They were also much in demand in the UK. Today there are three touring walls, some still operated by the original families that started them back in the 1920s.

The first recorded motorcycle stunt display was in 1928, performed by the Royal Signals Motorcycle Display Team. At the time, despatch riders were a key part of the army’s communication infrastructure so they needed to be extremely confident riders. Demonstrations of precision motorcycling soon became popular with the public, and despite a pause during the Second World War the display team has entertained audiences in the UK and abroad ever since.

Over the years the team has been known by many names – originally they were called the Red Devils (that name was eventually claimed by another display team…), before becoming the Mad Signals, finally settling on the White Helmets in 1963. Training hard during the winter, throughout the summer they are a regular sight at motorbike stunt shows up and down the country.

The Golden Age of Stunt Riders

The Human Fly

His early motorcycle stunts were based on being strapped to the outside of a jet plane, enduring speeds of hundreds of miles an hour. In 1975, while attempting this stunt in Texas, the plane had accidentally flown through a freak rainstorm. The impact of the raindrops at that velocity could have seriously injured him – he later claimed to have been in hospital for two weeks following the incident. Regardless, the public’s attention had been well and truly captured. Marvel comics picked up the rights to the character and he became the first real person to have a superhero comic published about them. His comic was written by Bill Mantlo, creator of Rocket Raccoon, most recently seen in Guardians of the Galaxy.

His third attempt at jet-riding was captured on video. The aim was to break 300mph, which they said they did although there is no evidence they went faster than 253mph. That’s still pretty fast.

Later in 1977 he was booked for the half-time show for a disco concert in Montreal’s Olympic Stadium. They wanted to beat Evel Knievel’s motorcycle jump record of 13 school buses not by one or two, but with thirty-six. To enable him to do this, the Fly contacted Ky “The Rocketman” Michaelson. Luckily Ky talked the Human Fly down to a far more sensible number of buses to jump, a positively tiny twenty seven. Michaelson then got busy adding two rockets to a brand new Harley Davison. As he says in his account of the affair, after he’d finished the bike had over 6000 horsepower.

Come the day of the stunt, Michaelson had concerns as the ramps provided had not followed the blueprints precisely. Also, the size of the stadium meant they were unable to get a proper run up to the ramps. Furthermore, it was self-evidently dangerous to even sit on, let alone ride, a supersonic rocket bike.

Despite the danger, The Human Fly was not to be put off. Sitting at the foot of the ramp, he opened the throttle to full. The bike zoomed into the air. Because of the thrust and incorrectly set-up ramp, the bike went much higher than it should have, and stalled when he let off the throttle. The rear end dropped, arching the back almost completely backwards, hitting the landing ramp hard and crashing back down on to the Fly.

His early motorcycle stunts were based on being strapped to the outside of a jet plane, enduring speeds of hundreds of miles an hour. In 1975, while attempting this stunt in Texas, the plane had accidentally flown through a freak rainstorm. The impact of the raindrops at that velocity could have seriously injured him – he later claimed to have been in hospital for two weeks following the incident. Regardless, the public’s attention had been well and truly captured. Marvel comics picked up the rights to the character and he became the first real person to have a superhero comic published about them. His comic was written by Bill Mantlo, creator of Rocket Raccoon, most recently seen in Guardians of the Galaxy.

His third attempt at jet-riding was captured on video. The aim was to break 300mph, which they said they did although there is no evidence they went faster than 253mph. That’s still pretty fast.

Eddie Kidd

Eddie Kidd’s stunt career was filled with amazing highs and one particular low. His film career began in 1979, jumping a 120 foot railway cutting for the now almost entirely forgotten Harrison Ford film Hanover Street. He then had the lead role for the 1981 comedy Riding High, as a courier who gets involved in a plot built around doing a large motorcycle jump over a derelict bridge. The rest of the eighties saw him take world records for jumping over buses and cars as well as doing stunts for movies and television, including James Bond and Doctor Who. He also dabbled as a model and a singer, as well as appearing in a Levi’s advert and a video game.

In 1993 Eddie Kidd jumped the Great Wall of China, and was then challenged to a jump off by Evel Knievel’s son Robbie, who deemed that only Eddie was worthy of challenging his jumping abilities. Eddie won that contest by six feet.

And then in 1996, tragedy struck. While performing at the Bulldog Bash, he landed awkwardly and knocked his chin on the petrol tank of his bike. This left him unable to stop his bike carrying on up the embankment past the landing area, or stop himself from falling off when it reached the top. He sustained serious head injuries as a result of this, and was left in a coma. Doctors told his parents that he could be in a coma for ten years, but he regained consciousness within three months. He was, however, left paralysed and with brain damage, and told that he would never walk again.

Since then, he has been striving to prove them wrong. In 2011 he undertook the London marathon, using a specially designed tricycle. It took him 46 days to complete the course, during which he raised over £100,000. The money was split between Children With Leukemia and his own charity, The Eddie Kidd Foundation, which aims to support the treatment and rehabilitation of stunt performers and extreme sportspeople.

Evel Knievel

If anybody has a claim to being the most influential stuntman in the world, it’s Evel Knievel. From jumps in front of Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas to nearly dying while attempting to cross the Snake River Canyon in a custom rocket/cycle hybrid, his escapades would be scarcely believable if we didn’t have film of them happening.

A consummate showman and a natural daredevil, Bobby Knievel got his nickname after being arrested for reckless driving around his hometown of Butte, Montana. When checking the cells, the night jailer noted that Robert Knievel was in one cell while the one next to him held a William Knofel. Knofel was already known as Awful Knofel, so giving Bobby his own rhyming nickname was inevitable under the circumstances. He later changed the spelling to Evel as he didn’t want to be considered evil.

Before he discovered his calling as motorcycle daredevil, it’s fair to say he got around a bit. For a while he managed a hockey team. His career highlight involved bringing the Czech national team to Montana – at the height of the Cold War, no less – and then disappearing with their money. Following that he started a hunting company, which went well until he was discovered going into national parks to hunt – poaching, essentially. Inspired by this, he hitchhiked from Montana to Washington DC with a petition calling to have elk relocated to areas where hunting was allowed.

On returning home, he had moderate success on the Motocross circuit, then became an insurance salesman, before opening a Honda dealership. It was then that one of his Motocross pals taught him how to do a wheelie.

Evel began touring the country with his motorcycle stunt show. In an attempt to one-up the competition he performed more and more impressive stunts. Many times he would crash and injure himself, but ever the showman he would jump straight up and tell the crowd about his next, even crazier stunt. He’d regularly return to towns where he failed and attempt the trick again, once he’d healed up.

His big break came in 1967. Evel Kenievel arranged to jump the fountain at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, a distance of 141 feet. He crashed, breaking his leg and pelvis, but the film of the stunt was spectacular.

Throughout the seventies he continually raised the bar with his stunts, breaking records as well as most of the bones in his body. Occasionally he would even make a successful landing. In 1971 he jumped the Snake River Canyon in Idaho on a steam-powered rocket cycle. He almost succeeded, but was dragged back into the ravine by the parachute, narrowly missing landing in a river. Had he done this, he would have drowned.

1975 saw him visit Great Britain where he jumped 13 double decker buses in Wembley Stadium. He crashed, breaking his back in the process. He then walked out of the stadium. He finally retired from stunting full time in 1977 following an accident in rehearsal for a jump over a 90ft tank of live sharks. During the rehearsal for the jump, he lost control and crashed into a cameraman. Evel broke both his arms, but was wracked with guilt by the cameraman who lost an eye in the collision.

It wasn’t all thrills and spills, in private Evel Kenievel battled with addictions. In the mid-seventies, at the height of his fame, he attacked a biographer, who claimed he was abusive to his wife and children, with a baseball bat. 2015 saw the release of a new documentary produced by Jackass supremo Johnny Knoxville. Being Evel doesn’t shy away from its subject’s darker side, while celebrating his achievements and the effect he had on society at large.

Doug Domokos

Doug Domokos certainly worked hard to earn his nickname, The Wheelie King. His motorbike stunt career began in 1975 at the Red Bud track in Michigan. He was part of a trio who’d perform wheelies in between races. After the trio split the following year, he continued solo, winning a wheelie contest at Santa Fe Springs, California. As word of his stunting skills spread, he was first signed up by Kawasaki, performing at stadium events throughout America.

In 1982 he moved to Honda. 1983 saw him perform the world’s highest wheelie, atop the Empire State Building. The following year, he won a $10,000 bet with a promoter by wheelieing a complete lap of the track at Anaheim Stadium. He went on to get a Guinness world record after wheelieing 145 miles at Talladega in Atlanta. He also appeared on national TV wheelieing up and down San Francisco’s notorious Lombard Street.

In addition to these big showpiece stunts, Doug was in demand as a stunt rider for movies and TV. He appeared in Cannonball Run, On Any Sunday 2, and cheesy cult classic Megaforce. He also made a guest appearance on the TV series The Powers of Matthew Star, which would later go on to be voted 22nd worst TV program ever made.

Sadly, Doug Domokos died in 2000 in an ultralight aeroplane crash.

John Taylor

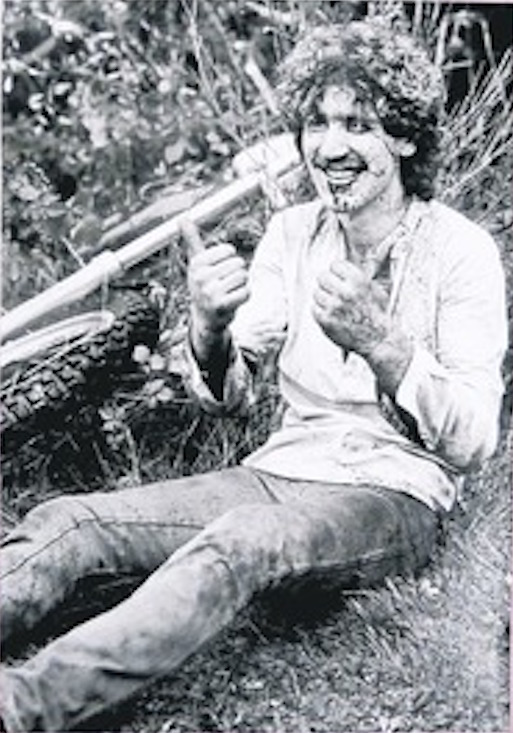

A leap out of darkness

It was a grey autumn day in 1985 and John Taylor was feeling uneasy.

Sitting astride his Moto Gori stunt-bike, the 21-year-old was staring along the rooftop of a derelict block of flats on the outskirts of Liverpool, a home-made 16ft-long ramp between him and possible death.

There were no medics, no safety stewards, and no TV cameras there to record the illegal jump from one doomed block of flats, over a second and on to a third, which dropped 30 feet below.

“I wasn’t in the mood for doing it – it was a grey October day, and I like to jump when the sky is nice and clear,” recounts Taylor.

“I knew I was gonna hurt myself and I didn’t want to do it, but I knew I had to.”

Taylor and 10 friends had defied police to set up the jump that would nearly cost him his life; a leap into the unknown, and a potentially suicidal protest against the abuse he suffered in a Catholic children’s home.

“I was on a mission to secure a good background for myself, so I could be taken seriously,” says Taylor.

“There was no money in it for me. It wasn’t about money and anything good that came out of it I would push away – I didn’t want to know because I didn’t want to be famous.

“The energy and the motivation that was pushing me wasn’t a nice energy and it wasn’t meant to be.”

Like many children growing up in the 1970s, Taylor was entranced by the exploits of Evel Knievel, and watched the great man’s legendary bus jump on TV.

While most of us were content to vicariously enjoy the thrill and move on as World of Sport cut to Big Daddy and Giant Haystacks grappling in the wrestling ring, Taylor was different.

“As soon as I saw it I thought, that’s what I’m gonna do. I’d always loved bikes, even before that – a bike to me was freedom,” he says.

A world record at 18 followed, jumping a 125ft wall of fire, before Taylor’s stunts took on a more maverick, and dangerous, element.

In 1982, Eddie Kidd jumped the viaduct over the River Blackwater in Essex for the film Riding High, and anything that Eddie could do…

“I can do that one but I’ve got to do it differently from the way he’s done it. We travelled down there, three of us in a van, got there late at night, we set up early in the morning and the way I did it differently was just by wearing a pair of jeans and a t-shirt,” explains Taylor.

“No helmet, no safety landing gear. The way I was seeing it at the time was that if you make it short, the helmet is not going to do you any good anyway. You’re finished anyway.”

He didn’t make it short, of course, and the jump was immortalised by local photographer Clive Tarling, who had received a tip-off from a friend in Fleet Street that a young lad from Liverpool had phoned up to say he was going to repeat Eddie Kidd’s jump – but without any safety precautions.

Speaking to the Essex Chronicle, Tarling remembered seeing “the feebly-constructed ramp on the other side of the disused railway bridge covered with plastic sheeting, which made me a little concerned”.

“I set up my camera with a wide-angle lens anticipating that I could shoot the entire jump sequence without moving the camera,” said the photographer.

“When I heard John’s bike revving up and as he approached the ramp constructed of metal building scaffold poles and scaffold boarding, I pressed the camera button, holding it down, the motor-drive kicked in enabling me to take a series of shots of the event. Back in the photo darkroom I printed the six best pictures of the motorbike’s trajectory and then I spliced them together to form a collage.”

Police and ambulance rushed to the scene as Taylor’s bike smashed into brambles on landing – the ramp having immediately disintegrated on take-off – but when they got there the grinning, oil-splattered teenager was already posing for Tarling with his thumbs up.

Success bred greater confidence, and a desire to go one step further. A plan to jump the eight lanes of the M62 on a quiet Sunday morning, from one field to another, was hatched and Taylor set off on a reconnaissance mission.

And that’s how he ultimately found himself facing the jump of his life, a jump that the famous TV daredevils he had grown up wanting to emulate would never have even contemplated.

Returning to Liverpool from his motorway recce, Taylor got lost.

“I ended up coming back through the Netherley area. I’ve seen all these high-rise derelict flats, all empty ready to be demolished,” he remembers.

“I thought OK, this will be a good one, I can jump from one to the other. There was a set of three where you had to clear the middle building.

“The third building was roughly 30ft smaller than the other two, the one I’d take off from and the one I’d jump over.

“The height I’d gain and the height I’d have to drop was about 60ft on to solid concrete doing about 75mph.”

Without permission from the council, who owned the buildings, police stopped the initial attempt. But three weeks later, with clouds hovering over the buildings, Taylor and his band of helpers returned to the bleak urban landscape.

“We kept knowledge (of the jump) to about 10 lads. I didn’t tell my mum, she wouldn’t have been happy. We set the jump up and we had to pull the bike up the side of the high building, 10 of us pulling it up.

“One nearly fell over the edge, but we got the bike up the night before the jump because we were going to do it at 9am the next day.

“We set up at 7am, and sealed off the top of the roof so police couldn’t come and take us off. I noticed a lot of cars and people gathered around the bottom.”

Then all that was left was the sound of the motorbike’s revs, the sight of the run to the ramp, the towering middle building, and empty grey sky beyond. Taylor was to come within inches of death.

“It comes to the big drop and I’ve seen it coming. The bike bottomed out (on landing) and my back took the rest,” he says.

“There was a 12 inch parapet around the top of the roof, which actually saved me from falling off because I’d fallen into that.

“The second I landed I felt the pain was tremendous – it felt like every organ had fallen off its holding and splattered to the ground.

“I felt the snap in my back and all of a sudden it was just complete darkness. It felt like I was getting my head kicked in.

“If you can imagine a mask and you can’t see anybody and there’s about six guys kicking you, with heavy boots on, as hard as they can, that’s what it felt like. At that point everything just went, no pain, no nothing, into darkness.

“There were a few friends on that roof that didn’t take it good at the time; it was a bit of an experience for them. The lads were doing CPR – it seemed like hours and hours before they took me off that roof.”

Taylor had broken his back in four places, plus broken ribs, ankles and wrists. But he was lucky to be alive.

“I knew I’d smashed myself up too far on this one,” he says. “If I’d have thought I was going to break my back in four places, ankles and ribs and everything else I wouldn’t have done it.”

A slow journey to hospital, TV interviews, and a visitor roster full of family, friends and ex girlfriends passed in a blur, and Taylor’s main concern was walking again.

“I could feel my feet, but I was worried about being able to walk – my own mind was telling me you’ve got to get up and keep going.

“I was in hospital for two days but they wanted me in for a few weeks. But being me at the time I signed myself out of hospital, got a taxi, went home, laid up for a while and tried to work out how I was going to get myself ready again.

“In my own mind I could see the damage to my back, and my own mind was trying to heal it up and in some weird way it has. I should be in a wheelchair now with the injuries I sustained on that one jump. It still hurts, it’s never going to go away but I have my ways of dealing with it.”

Time healed not only the physical wounds, but the mental ones too, and in 1999 Taylor was back on his bike at Southport beach. Another jump, another crash, and another broken vertebrae.

Stunt riding is a hazardous business, with injury always more of a probability than a possibility, but while the household names were rewarded with fame and fortune, Taylor leapt out of the darkness of a traumatic childhood, seeking emotional salvation and a way to bring the crimes inflicted on him and 12 other innocents into the light.

It was a fight they ultimately won in court; the pain had been worth it.

* The story here was originally told in a documentary as part of Liverpool’s Cinemacity project, and in a BBC Radio Merseyside interview

Modern-day Stuntmen

Robbie Maddison

Robbie “Maddo” Maddison has held a number of records for jumping the longest distance on a motorcycle, and in some of the most iconic locations in the world. He’s also made a bit of a habit of breaking records he himself set.

In 2007, forty years after Evel Knievel jumped over the fountains at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, Maddo was invited to recreate Knievel’s feat, which he did, setting a new world record in the process. The following year, he broke his own record three times in one night, going from 96.32m, to 104.42m and finally 106.98m. Next up, and a return to Vegas saw him performing a 29m vertical jump onto a replica of the Arc de Triomphe. 2009 also saw a trip to the UK and a Robbie Maddison midair backflip while jumping an open London Bridge. 2010 was the year he jumped the start gantry at the Grand Prix track in Melbourne, as well as the Corinth Canal in Greece. San Diego was the big jump in 2011, 400 feet over the bay.

He also doubled as Daniel Craig for the motorcycle chase in Skyfall, for which he won a prestigious Taurus award for best stunt with a vehicle.

Kevin Carmichael

Modern stunting is a rapidly evolving scene, taking its cues from skating and BMX culture as well as extreme sports. Most of the big names are young, as you’d expect from a sport where preparedness to fall off a moving motorcycle is a requirement of learning how to do it. One of the people who’ve been there since the early days of the sport is Kevin Carmichael. After starting to ride at the age of seven, he went on to become Scottish Motocross champion. His motorcycle stunt riding career began in 1997, which saw him take home the European Championship, a feat he repeated between 1999 and 2002. He’s also won a world championship as well as a host of other awards. Kevin was the first person to wheelie a superbike with no front wheel or forks, as well as the first person to do this with passengers! He’s currently Triumph’s official bike stunt rider, travelling the world delighting and astounding audiences with his tricks.

Streetbike Stunters

While freestyle motocross has become popular in recent years with the rise of tours like the Red Bull x-fighters show, streetbike stunting has taken a slightly lower profile. Its rise has been hampered by a number of factors. Firstly, anybody looking to learn how to do motorbike stunts has to be OK with falling off a lot while they learn. Secondly, there are very few “proper” places to practice. Any would-be stuntman is looking at a long period of falling off their bike in empty car parks, private roads or old airfields before they get good. And if they do, they may get the chance to perform at shows for less than spectacular fees. While there are a few stunt riders who have got sponsors and are making a decent living out it, it’s still a pretty niche area.

The majority of the “big” riders at the moment are European, and young. Head of the pack is probably Sarah Lezito, a 22 year old Frenchwoman. With over 2 million fans on Facebook, Sarah Lezito regularly wows audiences across the continent with her skills. Recently she doubled for Scarlett Johansson in The Avengers 2, and is due to feature in Ron Howard’s Inferno in 2016.

Her male equivalent is Rafal Pasierbek. The 29 year old Pole also began riding at a young age, catching the stunting bug after seeing videos on the internet. He entered his first stunt competition in 2005, winning outright. In the years since then he has won practically all the major competitions. Since 2014 he’s had a sponsorship deal with Yamaha.

Despite the hurdles to overcome, UK stunt riders are starting to come through, with talents like Joe Ephgrave, Monika Koch, Paul Jennings, Mark Van Driel starting to make names for themselves.

Streetbike Stunters

You’d be forgiven for thinking you need the power of a full motorbike to be a full motorcyclin’ stuntist, however there are at least two people who have made scooters their weapon of choice. First up is Nicola “L’impennatore” Campobasso, an Italian guy who likes scooters. Hard to believe but it’s true, I swear. And wheelying too – L’impennatore, we are reliably informed, means something like “the wheelie guy”. His talent for scooter stunting has developed over time, since the age of sixteen. In 2012 he was on Italy’s Got Talent. He claims to be the first person to have done many tricks on a scooter, including the backflip.

The other big name in the field of scooter stunts is Günter Schachermayr. Günter isn’t just satisfied with wheelies or jumping on scooters, he’s pushing the limits of what’s possible. For example, he bagged a Guinness World Record in 2014 for the highest ride on a steel cable – nearly 45 metres off the ground! 2014 also saw him grab a record for wheelying on high alpine roads and for the world’s steepest scooter ride, up the ski jump at the Bergisel ski run. 2015 had him riding on the Vienna Ferris wheel as well as planning his biggest stunt to date – riding a cable 4150 metres above the ground. Not only that, he’s also training towards driving his scooter across a lake underwater, as well as making attempts on the Vespa speed record.

In September 2015 he used a Ferrari to tow his scooter up to 120mph (200km/h). His stated aim is to be the first – and, to be honest, probably only – man to ride a scooter in the troposphere. While he’s technically doing that already, he presumably means riding at the planetary boundary layer, which is generally considered to be about a mile above the surface of the earth. This will, almost certainly, be impossible, but it should be entertaining watching him try.