When Richard Mummery was first offered the chance to buy his Wilkinson Touring Motor Cycle (TMC), his immediate response was “what the hell’s a Wilkinson?”.

You’d be forgiven for thinking the same, given the company famous for swords and razor blades made only about 250 motorcycles between 1908 and 1916.

Just four known Wilkinsons survive in the UK, two of which reside in the National Motorcycle Museum, with another in a private collection in Germany.

So unless you’ve visited the museum, live near Richard’s home a few miles from Canterbury, or near the route of the annual Pioneer Run, the chances are you’ve never seen one.

As soon as Richard saw the Wilkinson motorcycle, he said “yes please”

When he first set eyes on this remarkable machine back in 1982, Richard was no stranger to old bikes, already owning a 1929 BSA 350 Sloper.

But this was something else entirely, even if it was only “loosely assembled” having been off the road for quite some time.

“As soon as I saw it I said ‘yes please’,” says the retired engineer-turned-driving examiner, paying £2,500 for the 1913-manufactured bike.

“It was a hell of a lot of money in those days, but it’s worth a bit more than that now…”

With help from Wilkinson Sword’s historian, the late John Arlett, “a mine of information”, and assorted engineers, Richard got the veteran bike back on the road.

Over the past 40 years, he’s ridden the olive green bike, powered by a water-cooled 848cc engine of the manufacturer’s own design, thousands of miles on the Pioneer and Banbury runs in England and the Oude Klepper Parade in Belgium.

Now 83, Richard’s days on the heavy bike on the longer runs may be over, but he has no immediate plans to sell one of Britain’s most rare veteran motorcycles.

Fascinated with motorbikes from the age of 10

“I love it to bits,” he says. “I don’t want to get sentimental, but sometimes I’ve just got to stand there and look at it.

“When the time comes, I would like to sell it to someone who is going to ride it. I’d hate it to go to a museum.”

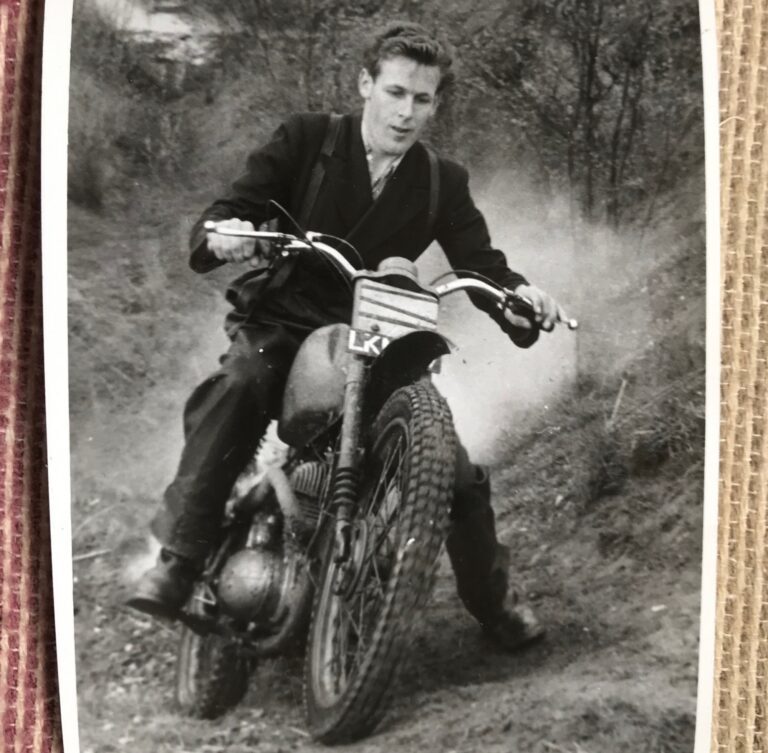

Richard’s fascination with motorbikes began at the age of 10, when he would help his older next door neighbour clean and look after his early BSA Bantam D1.

“I occasionally got a ride on the back of it, and I got to learn a bit about bikes,” he says, including when things go wrong.

“He’d had it about a year and decided it needed a de-coke, but when we put it together again it had got no compression at all and wouldn’t start.

“He said ‘take it apart again’ – he was a bit of a spoiled brat – so I took the exhaust system off and as I moved it I heard ‘tinkle tinkle tinkle’.

“We lifted it up and all these little tiny parts of piston ring came out. We’d somehow managed to get the barrel on without the piston ring ends being in line with the gap.

“He gave me some money, I went into Canterbury and bought a new piston and rings, and that was successful.”

Buying his first motorbike

Richard started work at 15 as an apprentice bus engineer at the East Kent Road Car Company, and a year later bought his first motorbike: a 1953 plunger frame James.

“Some of the other lads there had bikes, so it was a case of joining in,” he says, keeping the James for a couple of years before buying a 1954 AJS 350 Jampot from a colleague and joining the Birchington Motorcycle Club.

“One Sunday we had an off-road trial and one of the club members let me have a go on his Greeves. I was hooked. I never progressed much, but I managed to get to expert status in the south eastern centre, riding in local trials at weekends.

“My first trial bike was a 197cc Norman, then I progressed to a 350 AJS which was a lovely bike. I did quite well with that, but never won any terrific awards, just first and second class awards.”

Called up to National Service at 21, Richard was to enjoy success in trial competitions in the army.

Because of his engineering background, he was drafted on to the Queen’s Own Buffs’ motor transport section, which looked after six Bedford RL trucks, the same number of Austin K9s, and 10 girder fork BSA M20s.

While training at Maidstone, Richard discovered the battalion had a successful trials team while stationed in Cyprus.

Practising on the BSA M20s

“My ears pricked up, and two of the lads were national servicemen,” he remembers. “Thursday afternoon was sports afternoon, and we had nothing to do so I persuaded them to let me come out with them and we’d go out on the M20s, practising.

“When the two national servicemen demobbed, I managed to get into the team. I had the luck of Old Nick and every army trial I rode in, I won something.”

Riding his standard army issue M20, with normal road tyres, Richard qualified for the national army trial championships in both of his two years of National Service – competing in Wales and at Liphook in Hampshire.

In his second year of service, the battalion travelled to the Stanford Training Area (STANTA) near Thetford in Norfolk, Richard helping to marshall the convoy of trucks.

“Once we got to Thetford, the three of us on motorbikes had nothing to do,” he says, “so we started playing around doing trials.

“Somewhere up the road was a duck farm, and one of our lot, a scoundrel, pinches a couple of ducks and kills them to supplement our menu. He plucked them, and there was duck down everywhere.

“The next morning, I was called to the office thinking ‘we’ve been found out’. But he said ‘you’ve been selected to ride for the south eastern area in the army championships at Wales’.

Riding on the M20 with a sten gun

“I got a second class award, and was then excused from all duties and told I could go home. I rode on my own from Thetford to Kent on this blasted M20 with a sten gun, semi-concealed, and petrified going through the Dartford tunnel, thinking somebody’s going to jump on me. I buried it in the garden when I got home!”

After leaving the army, Richard continued to compete in trials for a while until marriage and children came along, and motorcycling took a back seat.

He worked for a decade as a fitter for a small coach company before training as a driving examiner, initially based at Grays in Essex and commuting in a Rover 2000.

His first step back into bikes was a New Hudson autocycle, bought from an “old gentleman” who had just passed his driving test.

“He said ‘oh good, I can get rid of my autocycle now’,” says Richard. “I had his contact details, and about a week later I phoned him up and bought it.”

Many bikes followed, including a Triumph Saint

The 98cc bike clearly wasn’t man enough for the daily commute, and was used mostly for shows, but the ex-Liverpool police Triumph Saint that followed was definitely up to the job.

“I bought it complete with the police fairing, everything,” says Richard. “But it was shot to pieces. They’d really worn it out. I rebuilt it in a month and used that to and from work.

“It was much quicker, and cheaper to go through the Dartford tunnel.”

After getting a transfer to Gillingham, and then Canterbury, Richard moved from car driving tests (nine a day) into heavy goods vehicles (three a day).

The Saint gave way to the 1929 Sloper which, in turn, led Richard to joining the Vintage Motor Cycle Club (VMCC).

“One summer evening I rode up to where they met once a month in a village 10 miles from here, and I was very disappointed because everyone was on ‘50s and ‘60s bikes,” he says.

“I was the odd one out. This prompted one or two others to get their vintage bikes out and we did a couple of girder fork runs.”

One day in 1982, after riding the Sloper to work at Gillingham, Richard was offered the chance to buy the Wilkinson by a friend of the bike’s owner, Derek Ince, who had just died.

Having got the bike home – “it was easier to carry in bits” – the real detective work began.

Making friends with Arlett, Wilkinson motorcyclist and company historian

A phone call to Wilkinson Sword initially drew a nonplussed response, until Richard’s enquiry eventually landed on the desk of Arlett, sword designer and company historian.

“He came down and he was over the moon that another Wilkinson had come to life,” says Richard. “ He was a motorcyclist as well, so I could talk to him as a motorcyclist, and he put me in touch with another owner, Norman Cullen, in Greater London.

“He had a beautiful one, but with the sidecar. We became good friends and he helped me a great deal, but sadly he’s since died.”

Wilkinson’s first motorcycle was produced in 1908, a military scouting model complete with a quick-firing Maxim machine gun on the handlebars.

Rejected by the British army, the company continued development of a road version, the air-cooled, 678cc Touring Auto-Cycle which, for a while, was fitted with a steering wheel instead of handlebars.

For the new model, the Touring Motor Cycle, the engine was upgraded to the water-cooled, 848cc in-line four-cylinder side-valve found in Richard’s example.

War stops production

Production was brought to a halt with the outbreak of the first world war, when the company was forced to produce thousands of bayonets for the war effort.

The engine in Richard’s bike was in “a very poor state” when he started to investigate.

“It looked like they were the original pistons, but there was wear, and I took the four cylinder barrels to my local reboring specialist having not bothered to measure them,” he says.

“I dropped them in and said ‘can you bore these to a standard size?’ I had been home for barely an hour and he phoned me and said ‘there’s only two of these cylinders that are the same size.’

“I asked him to bore them all to the biggest size, and I’d get pistons made. Got pattern pistons, luckily – a friend of mine in Gravesend, a super engineer, made them up for me.”

The bearings had to be hand-made, some existing valves were modified to fit, while the three-speed gearbox needed little work.

Braking is on the rear wheel only, a dual system featuring an internal expanding brake and a band brake on the outside of the same drum. Again, all it needed was tidying up and renewing.

Not so the car-style seat, which was virtually non-existent.

“Luckily, Norman had got the original, so this seat is an exact replica, even down to the correct number of pleats,” says Richard.

“The fuel tank the previous owner had made for it was rusty, but it was good for a pattern. Then it was just a question of painting it all. They did them in black, grey and olive green. Mine is an olive green very close to Norman’s – not quite the same, but it was a colour I liked. There are not too many people who are going to say ‘that’s the wrong colour…’

Getting the Wilkinson back on the road

“I had lots and lots of help from people who are much better at engineering than myself, and eventually we got it all together.”

The Wilkinson had been off the road for so long that Richard needed to get it registered and, with Arlett’s help, tracked down some of its history.

“We found out it was first registered in Essex, so I contacted the Essex county registration office and they had records going back,” he says. “I was able to get its original registration number.

“Its first owner was a South African who went back home after the second world war, and it would seem that Derek Ince, who I bought it from, bought it from him.”

Its maiden voyage involved a certain amount of trial and error, and ended in a cloud of smoke.

“I had no idea how much oil it should hold,” says Richard, “and there was no dipstick at the time, so I three-quarters filled the oil tank and I must have overfilled the sump.

“We push-started it on a nice downhill section of road, and it fired up very quickly but you couldn’t see for smoke, and oil was coming out of every orifice possible.

“There were three of us, and they said ‘leave it running, it can’t come to any harm…let it stand there until the oil has stopped coming out’.

“I wiped it down and got it back home, and there was a threaded area so I could make a dipstick plug up. That’s how I found out how much oil it needed, and I’ve kept it like that ever since.”

Riding the old machine had a “very steep learning curve”

As for riding such an old machine, Richard says it was “a real handful, a very steep learning curve”.

“I think the first event I rode it in was our local VMCC Sittingbourne run,” he adds. “Oh dear. It’s all through country lanes, uphill and downhill and, my God, was it hard work. Because it’s so heavy, the manoeuvrability was horrendous.

“Because I knew the area I cut one or two corners and got back to the finish.”

On another Sittingbourne run, a thunderstorm broke out just after the start, and the old bike ground to a halt.

“I sat at the side of the road, and the storm lasted for quite a long time,” says Richard. “The sun finally came out and I tried various things to try to start it, but it wouldn’t start.

“Eventually, I thought, well I’m not far from the finish, I’ll take the magneto off, turned it upside down, and I couldn’t believe the amount of water that ran out of it.

“I blew it dry with my mouth and the bloody thing started, so I rode the mile and a half to the finish. The magneto now has a rubber cover over it.”

Over the past 40 years, Richard has completed 30 Pioneer Runs, organised by the Sunbeam Motorcycle Club and open to veteran bikes manufactured prior to 1915.

The course runs nearly 50 miles from Epsom to Brighton and, along with the Banbury Run (on which Richard is also a regular), represents an annual highlight of veteran motorcycling.

“I’ve always done it because I see so many friends and acquaintances, and you also get quite a few continental riders come over,” says Richard, recounting the perils of mixing ancient machines with modern traffic.

“For the last mile or so into Brighton, you have to transfer across to a three lane road, and that’s very hairy. You’ve got stuff coming down at 70 and 80mph and you’re doing 35 to 40. Some riders on 1903 or 1904 vehicles are flat out at 20mph.”

Wilkinson is remarkably reliable

For a machine of such great age, it’s been remarkably reliable, although it has had its moments, including on one Pioneer Run when Richard and his support driver simply could not get the Wilkinson to start.

“He was a big fellow, a good push starter,” he says, the hand lever starter rarely working on these old bikes.

“It was early spring in Epsom, a freezing cold wind, and we pushed it up and down but the bloody thing would not start.

“Eventually, I decided – I don’t know why – to take the main jet out. It was blocked and, after I cleared it, it burst into life straight away. My co-driver clipped me round the ear – we’d pushed it hundreds and hundreds of yards!”

On a Banbury Run one year, Richard was within three miles of the finish when, “oh dear”.

“Normally the routes are designed for bikes with not too good brakes, but this year I was on a steep downhill section,” he remembers. “I was unsure of how steep the hill was, and I braked ever so hard with the foot brake. For some reason the brake shoes hopped off the cam and sat on top of the support either side, so it was jammed on.

“It’s a good half an hour to take the wheel out, and three quarters of an hour to put it back in. So unfortunately I was trailered back to the finish.”

Veteran and vintage bike collection

Over the years, the Wilkinson has been joined by other veteran and vintage bikes in Richard’s shed, all kept under fire-proof blankets and surrounded by dehumidifiers and memorabilia.

From 1914, there’s a Model W Triumph and a Douglas and another, almost identical, Douglas from 1922, as well as a 1937 AJS 250 on which Graham Walker – accomplished racer and father of commentator Murray – won a race at Brands Hatch.

These days, they are all rather more manageable than the long and heavy Wilkinson but, from time to time, Richard can’t resist the allure of firing up the old girl.

“I attend jumbles and, at Romney Marsh, they have a bike show and a huge grass field,” he says. “Last summer, the bike was standing there and at the end of the show I was loading up my jumble when a couple of old boys said ‘I don’t suppose the bloody thing goes’.

“I had a pusher with me, and we did three laps of the field. Julie, the organiser, said ‘why didn’t you do that at 10am when there were more people here?!’”

With so few Wilkinsons around, Richard plays down his position as marque specialist for the VMCC.

“It sounds grand, but since I’ve taken on the job I’ve done nothing apart from, every now and again, putting a note out in one of the motorcycle magazines asking for any Wilkinson owners to come forward,” he says. “I’m sure there’s another one tucked away somewhere.”

As for this Wilkinson’s next chapter? Anything but a museum.