As a teenager, Barry Burrage had no intention of getting a motorbike.

“To be honest, I’d never wanted one – I considered them dangerous,” he says, surrounded in his rented unit by a collection of five bikes, with another one at home.

But, after leaving school at 15, he got a job 11 miles from home, and got tired of the daily pushbike ride.

“I wasn’t very keen on that, so it was decided that I would have a small motorbike until I could have a car,” he says, finding a 1951 James Comet languishing in a shed.

1951 James Comet is Barry’s most treasured possession

That was in 1969 and, more than 50 years later, and after a full restoration, the little bike that started it all remains Barry’s most treasured possession.

“If it hadn’t been for that I wouldn’t have all these, because I’d have never got into motorcycling,” he says. “If I’d have worked nearer home, I’d have probably waited until I could have a car and I’d have probably never had a motorbike. I owe that James all of the pleasure I get.”

Joining the James in the unit are a Triumph Trident T150, a BMW R100RT, and a 1949 Douglas Mark III, while a 1960 Norton Model 50 resides at home south of Norwich.

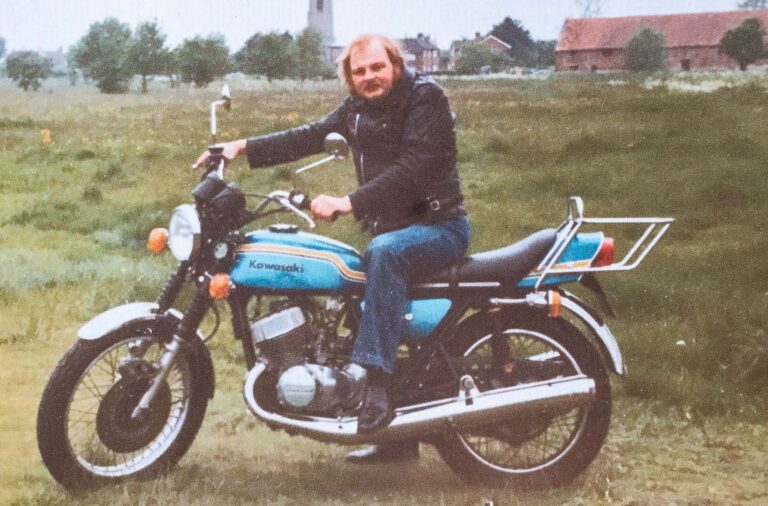

Barry says all these bikes are “replaceable”, but there’s one more that, like the James, has a special place in his heart – an unrestored Kawasaki H2 Mach IV 750 that he’s owned since February 1977.

Kawasaki H2 Mach IV 750 dubbed the “widowmaker”

The legendary two-stroke triple, the fastest 750 of its day, was dubbed the “widowmaker” in some quarters because of its extreme power and questionable handling and brakes.

“For their day they were very fast, and even today they’re quite quick,” says Barry, 67. “It’s become a bit of biking history. Unfortunately the brakes are not that brilliant, the handling is not that brilliant, and so consequently with the speed and the lack of ability to stop, or go round corners, they tended to have a lot of accidents.

“I knew its first owner and he had quite a severe crash on it. In fact, it was so badly damaged it was reframed. He very badly broke an arm, which took a year to heal, and he put two ribs through his lungs.”

Both the James and the Kawasaki, at opposite ends of the performance spectrum, have huge sentimental value, and Barry plans on keeping them long into his old age.

Irreplaceable bikes

“I’ve gone through too much life with them to sell them,” he says. “In that way, neither of those bikes can be replaced, because the money that can buy you another one won’t replace those memories.”

It all started in 1969, when Barry left school and became an apprentice commercial vehicle fitter at Mann Egerton on the northern outskirts of Norwich.

At the time he was living with his parents in a village a few miles south of the city, and the James – “not exactly a barn find but near on” – would save time, and energy, getting to work and back.

“One of the fitters from work came and helped me get the James fit for the road,” he remembers. “It took a few months doing odds and ends at weekends, mainly things like replacing cables, sorting out the wiring and giving it a good sort out and tidy up.

“He took it for an MOT for me and, on my 16th birthday, the 4th of January of 1970, off I went down the road. From that, the biking bug bit.”

The Comet, powered by a 98cc Villiers two-stroke, was Barry’s daily rider for only a few months before he bought a Triumph Tiger Cub.

“I kept it as a spare bike because Tiger Cubs are notorious for being unreliable,” he says, but “eventually it got to the point where it wouldn’t pass an MOT”.

“Mainly it was the wheel bearings, and you couldn’t buy them at the time.”

Consigned to the shed

The bike got shuffled to a corner of the garden shed sometime around 1973, and remained there until the early 80s when Barry started taking it apart for an aborted restoration plan.

After marrying Daphne in 1984, he planned to restore another somewhat shabby Comet (which he bought as a spares bike at 16) so they could have one each – but, again, the work was never completed.

Instead, Daphne rode Barry’s father’s Honda 125, progressing through to a 250 and then a Honda 500T.

By now, though, Barry had bought the Kawasaki, via several more Triumphs, the latest a 1955 Tiger 110.

“I decided to go Japanese because the Tiger was a 20-year-old dynamo model bike and, at that point, you couldn’t get any bits to repair dynamo stuff,” he says.

“The electrics on it were bad, the dynamo wasn’t charging the battery and once it went flat the lights stopped working after a while.

“It had been like that for months and months, but it didn’t bother me normally because I didn’t go far – I would come home on a battery and charge it up before going out next time.

“I went to Brands Hatch one weekend with the idea of getting home in daylight, but we got held up a bit and I ended up having to leave it behind a pub near Ipswich where the lights stopped working.”

After getting a lift home on the back of a mate’s Kawasaki 400 triple, Barry returned to the pub the next day and partially stripped the Triumph to lift it into the back of an estate car.

Getting a Japanese bike

“I thought ‘I’ve had enough – I’m going to get a Japanese bike’,” he says, initially setting his sights on a Suzuki 750.

“I was looking for one and couldn’t find one, and my mate had that H2. It was non running at the time, having broken down on him. He said ‘why don’t you buy that off me, you can have it for fairly cheap, and get it sorted…’

“I said ‘I don’t know, it’s too thirsty, it uses too much fuel’, but he said ‘it depends how you ride it’.”

Barry was persuaded, and set about getting the 1974-registered bike back on the road, which was easier said than done.

“I couldn’t find out the problem, so I had to take it somewhere, and they didn’t really know anything about it because they weren’t exactly commonplace,” he says.

“They messed about with it in between other jobs and, after a few months, they found the problem – a burnt out coil – but couldn’t get the part. I managed to get the part, they fixed it and I finally got to ride it.”

At first, given the bike’s hooligan reputation, it “didn’t live up to expectations”.

“But I then went back and relayed this to the person who was fixing it and he tweaked the carbs a bit,” says Barry, “and on the second ride I realised what I’d got, because the first thing that happened was the front wheel leapt in the air.

A wild ride

“It seemed difficult to keep the front wheel on the road in the power band in first, second or third. You could be going along in fourth, put it back into third, give it a handful and it would just come straight up. It was reasonably exciting…”

The bike was originally gold, but Barry repainted it Rootes Kingfisher Blue, unknown to him a very similar colour to the Kawasaki 250 of the time.

“There were times when people tried to tell me it was a 250 with 750 badges on it, but they changed their mind when it went,” he laughs.

As to its exact model, Barry explains that 1974 bikes should have been H2Bs, but he believes this is an H2A model imported from unsold stock in Holland.

“When my friend wanted one, no-one in England had any – there was a shortage,” he says. “He asked the Luton dealer (I think) if there was any way they could get one.

“They said they might be able to import one off the continent brand new, but it may have some differences. He said ‘I don’t care’, and they obviously went to Holland. I can only assume someone there had last year’s model standing in the showroom and couldn’t sell it, so they sent that one over. There are only a few minor differences, but they do say the early ones are quicker.”

The Kawasaki was Barry’s daily commuter bike, also taking in race meetings at Brands Hatch, Mallory Park, Donington and, occasionally, Silverstone, as well as evening and weekend rides out with friends.

Braving a European tour

In 1981, he braved a European tour, getting the ferry from Harwich to the Hook of Holland and heading for Amsterdam, then on to Brussels, Paris, Calais and home via Dover.

“I was constantly worrying about running out of petrol,” he smiles. “The other bikes with me were a BMW R100RS with a five gallon tank and 50mpg, and a quite economical 850 shaft drive Suzuki with a fairly big tank.

“After 120 miles, mine needed fuel again, and that’s if you don’t have it in the power band – if you do, it drains it at about 25mpg. It wasn’t good for touring…”

It prompted Barry to get a BMW of his own, first a former police bike from an auction and then the R100RT he owns today.

“I did consider selling it when I bought the BMW, but nobody wanted it, strangely enough considering what it’s like now,” he adds.

“So I didn’t sell it, and afterwards I thought I’d keep it. I still used it a lot of the time but if we went any distance I’d take the BMW because it was more economical.”

Biking hiatus

Unfortunately, Barry and Daphne split up in 1992, and there followed a dozen years of financial difficulty when he simply couldn’t afford to have a motorbike on the road.

The Kawasaki joined the Comet in the shed, and by the time Barry could afford to run a bike again, in about 2004, he thought it had been standing for too long to ride straight away.

“I thought it was going to be a bit of a job getting bits to fix it, because it used to be a job to get parts for,” he adds, buying the Trident T150 instead.

“Then six years later I pulled the H2 out of the shed and made a list. We had got the internet by then and, to my amazement, I got all the bits I needed, fitted them and took it for an MOT and it was back on the road. It didn’t need as much as I thought, and it only took me a fortnight to fix!

“It’s been on the road ever since.”

These days, the bike is used purely for pleasure, and Barry often meets up with hundreds of fellow bikers on the hugely popular Two Wheeled Tuesday event held weekly on the green at Old Buckenham in south Norfolk.

There, this well-used bike attracts arguably more attention than the smattering of pristine, restored Kawasaki 750s.

Back on the road with the Kawasaki H2 Mach

“The comments are usually ‘it’s nice to see one that hasn’t been overdone’, or ‘nice to see one that’s in ridden condition’,” he says.

“It makes me think ‘perhaps I won’t restore it just yet’. I would love it to be back to like some of those early photographs, but I couldn’t really afford to because those exhaust pipes cost a fortune. You can get pattern exhausts, but they’re fairly expensive. New old stock have occasionally turned up, but you’re looking at £600 for a silencer.”

Back to the Comet, and in 2019 Barry hatched a plan to get the bike back on the road for the 50th anniversary of his 16th birthday.

“I wanted to ride it on January 4, 2020,” he says. “That gave me the push. I’d always wanted to do it, but never got round to it. It spent nearly 40 years in pieces from when I stripped it down; but things got in the way, like getting married, getting divorced, having other motorbikes, working etc.

“In 2019 I just thought ‘that’s it – it’s time to sort something’, and I pulled it all out of the shed, laid it out on an 8×4 sheet of ply, put the frame on there, stuck the engine in the middle of the frame, put the tank above it, and so on in some type of exploded version to see if I had enough to be worth restoring. I realised there must have been more than 95 per cent of it still there, although admittedly a lot of it needed work.

“I set about doing it and this time actually finished it.”

The wheel bearings – the reason it was off the road to start with – presented a problem, because replacement parts were still unavailable.

“I had to make up conversions for all the wheel bearings to put ball racers in,” he says. “They are cup and cone like an old fashioned pushbike – they were obsolete 50 years ago – so I had to fabricate something.

“Most other stuff you could get, Villiers Services are still pretty good, they’ve got all the engine stuff you’d want, and a few other bits and pieces like exhaust systems.

“The cables and wiring harness, I made myself, and I converted it to charge a battery so I could put stop lights on that wouldn’t nearly go out when you slow up.”

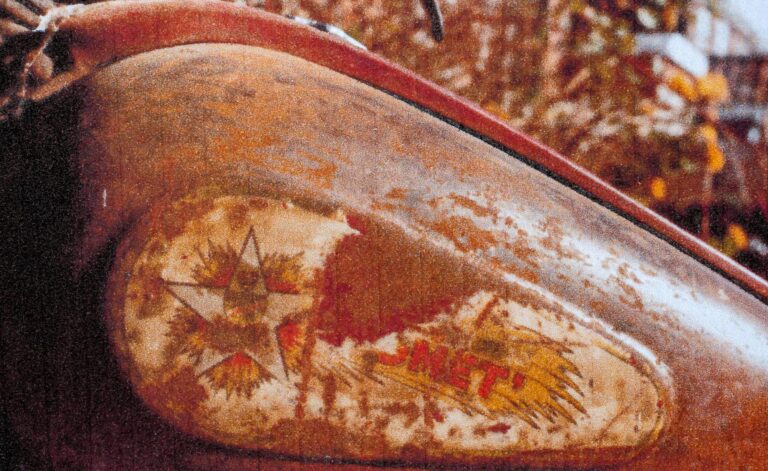

Unusual graphic

The seat was re-covered, the wheels given new spokes, and Barry gave it a fresh coat of paint, while a replica of the James transfer graphic on the tank was obtained from the Vintage Motor Cycle Club.

“I discovered it when I was rubbing it down,” he says, finding it beneath the “normal” graphic found on a Comet.

“I didn’t know it was anything different to what would have been on them until I rubbed down the tank off the spare one I had, and found the normal badge on that one.

“The man from the club transfer scheme said it was a one-year only thing, but no-one seems to have been able to tell me why.”

The bike is shod with new old stock Dunlops, which sat in the shed in their wrappers from the aborted ‘80s rebuilt, and remain “as soft as a baby’s bum, perfect, like new tyres”.

After a few months’ work, the Comet was ready for the road right on schedule, and Barry rode it for the first time in more than 40 years a week before his birthday.

“It was a strange experience, because I hadn’t ridden it since the early ‘70s and suddenly I took it out on the road and did about nine miles,” he says. “It sort of transports you back, the memory suddenly clicks and you think ‘I remember this, how it behaves and what it does’.”

Unfortunately, after getting it home from the workshop on a trailer, it failed to start up again.

“So I never got to ride it on my birthday, but I did the week before,” says Barry. “I’ve got it running again now though.”

He’s once again puttering about the Norfolk country lanes on the bike that started it all.